Takuo Yuasa & Ulster Orchestra

Biography Takuo Yuasa & Ulster Orchestra

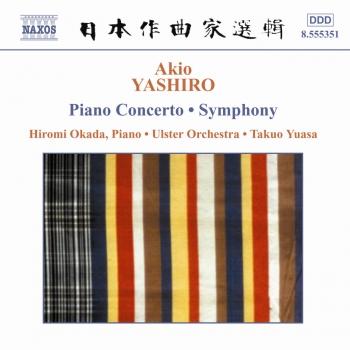

Akio Yashiro

was born in Tokyo on 10th September, 1929. His father Yukio Yashiro was a leading historian of European fine arts in Japan. He had studied in Italy in the 1920s, and his work on Botticelli had won high esteem, even among European scholars. His mother was a pianist. Brought up in the artistic environment provided by his parents, Yashiro began his piano lessons at the age of five, and, soon turning to composition, became a pupil of Saburo Moroi when he was ten. Moroi had studied in Berlin, and was composing works of absolute music in the form of symphonies, concertos, sonatas, and similar established forms. A great admirer of Beethoven, Moroi believed that the organic and strict development of a motif was all in all in music. From 1943 on Yashiro studied under Qunihico Hashimoto. The modernist Hashimoto introduced his young pupil to Debussy, Ravel and Stravinsky. On the other hand, at Gyosei High School, run by French Catholic monks, where Yashiro had his secondary education, he was trained in the French language.

In April, 1945, towards the end of World War II, Yashiro entered the Tokyo music school, the present Faculty of Music, the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music, and continued to study under Hashimoto. Under the same teacher was Toshiro Mayuzumi, who was later to become the champion of avant-garde music in Japan. Yashiro also joined the Kamakura Symphony Orchestra that Hashimoto conducted, and played the timpani.

In 1946, after Hashimoto had resigned from the Academy as a result of his war-time activities, he and Mayuzumi studied under Tomojiro Ikenouchi and Akira Ifukube, who replaced Hashimoto. Ikenouchi, who had studied under Busser in Paris and respected Ravel, taught his pupils to compose thoroughly polished music with perfect finish, while Ifukube, a pupil of Alexander Tcherepnin, who had particular attachment to ostinato and refrain, taught them precise and powerful orchestration using Stravinsky and Prokofiev for models, as well as inspiring them with a certain conciseness of expression. At the same time Yashiro became a pupil of the pianist Leonid Kreutzer, who had been living in Japan since the 1930s.

In 1951, Yashiro graduated from the Tokyo Academy of Music, and went on to study at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique de Paris. Mayuzumi was with him also at the Conservatoire, but deciding that there was nothing further to learn from French academicism, returned home after a year. To Yashiro, however, who had a kind of perfectionist orientation drilled into him by Moroi, Ikenouchi and Ifukube, and had been inspired with longing for France by Hashimoto, Ikenouchi and his early schooling, study in France proved highly beneficial. He studied under Nadia Boulanger, Tony Aubin, Henri Challan, Noël-Gallon, and Olivier Messiaen, and in 1955, he submitted as his graduation work, which happened to be his only composition from this period, a string quartet in the manner of Bartók. This work was praised by Florent Schmitt, Henri Barraud, and others, and was given its first performance by the Quatuor Parrenin.

After returning to Japan in 1956, Yashiro wrote for documentary films and drama, in this connection in a highly important collaboration with Yukio Mishima in a series of works, while at the same time helping such young composers as Teruyuki Noda, Shin’ichiro Ikebe, Akira Nishimura and many others to develop their talents at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music. Yet, because of his perfectionism and his belief in less prolific activity as a composer, he was able to write relatively few concert works, as Dukas and Lyadov had done. The only works of this kind he wrote after his return home were a cello concerto, a sonata for two flutes and piano, a piano sonata, and the two works recorded on this disc, a total of five works in all of absolute music. Every one of them, however, was a fine work of art, and together with the string quartet from his French period and some works before that, a violin sonata, a piano trio, and other works, remains in concert repertoire. Yashiro died suddenly of a heart attack on 9th April, 1976.

Yashiro’s Piano Concerto was commissioned by NHK, Nippon Hoso Kyokai, the Japan Broadcasting Corporation, and was composed between 1964 and 1967. It was first heard in a broadcast performance on 5th November, 1967, with Hiroko Nakamura as the soloist and the NHK Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Hiroshi Wakasugi, and was awarded the Odaka Award of the Year. Instituted in commemoration of the composer Hisatada Odaka, the award is the most important prize in Japan given to orchestral works. This work has ever since enjoyed particular favour in Japan among works written by Japanese composers, and has been played several times in the West. Among those who have conducted the concerto are Jean Martinon, Jean Fournet, and Michael Gielen.

The Piano Concerto consists of three movements, and there one can recognize the influence of Bartók, Prokofiev, Jolivet and others, as well as that of a Japanese composer who also studied in France and whom Yashiro regarded as his rival, Akira Miyoshi, notably his Piano Concerto of 1962 and Concerto for Orchestra written two years later. The first movement is marked Allegro animato and is in free sonata form. The piano abruptly starts playing the first theme like an incantation in irregular time, supported by the vibraphone and the strings, with characteristic interjections of two chromatically descending notes on the brass repeatedly thrown in. This is followed by a vigorous quasi-cadenza passage for the piano. Then the flute takes up the meditative first part of the second theme, which is followed by the piano playing the lament-like second part, in cadenza style. The development mainly takes up the first theme but only briefly as if it merely serves as an introduction to the recapitulation. The first half of the recapitulation, taking over from the development, treats the first theme, but with an increasing intensity, until it reaches the climax, which is highly reminiscent of Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 2. The second part of the recapitulation recalls the vigorous quasi-cadenza passage and the second subject group. The second movement is marked Adagio misterioso. The rhythmic pattern of seven notes in three bars in C only is repeated 43 times with a persistence that would overshadow Ifukube and Ravel’s Boléro. The motif of the second part of the secondary theme of the first movement joins in and the movement is brought to a climax, after which the music gradually fades away and is brought to an end.