Stravinsky: Symphony of Psalms San Francisco Symphony & Michael Tilson Thomas

Album info

Album-Release:

2020

HRA-Release:

10.01.2020

Album including Album cover

I`m sorry!

Dear HIGHRESAUDIO Visitor,

due to territorial constraints and also different releases dates in each country you currently can`t purchase this album. We are updating our release dates twice a week. So, please feel free to check from time-to-time, if the album is available for your country.

We suggest, that you bookmark the album and use our Short List function.

Thank you for your understanding and patience.

Yours sincerely, HIGHRESAUDIO

- Igor Stravinsky (1882 - 1971): Stravinsky: Symphony of Psalms:

- 1 Stravinsky: Symphony of Psalms: I. Prelude (Psalms 38, 13-14) [1948 Revision] 03:09

- 2 Stravinsky: Symphony of Psalms: II. Double Fugue (Psalms 39, 2-4) [1948 Revision] 06:16

- 3 Stravinsky: Symphony of Psalms: III. Alleluia (Psalms 150) [1948 Revision] 11:05

Info for Stravinsky: Symphony of Psalms

That a composition should have unique thematic material is a familiar enough idea, at least for the nineteenth and twentieth centuries; that it should, or even can, have a unique sonority is more specifically a Stravinskian thought. What Stravinsky calls for in the Symphony of Psalms is an altogether special distribution with unusual concentration on certain sounds (flutes, trumpets, and pianos) and complete omission of others (clarinets and high strings).

Stravinsky’s practice is opposed to the classic‑Romantic way of “modulating” organically from one event to the next. Instead, he proceeds by shock. He makes a deliberately violent leap from the clipped opening chord to a scurrying sixteenth‑note figuration and back to the chord. Another vital feature is the dynamic marking of that first chord, mezzo-forte. The force of the gesture is unmistakable, and every other composer would have expressed it with a smashing hammer blow of sound. Stravinsky turns its energy inwards, and the compressed, even repressed, nature of his expressive impulses provides an essential clue to the sources of the beauty and power of his music. The Symphony’s intensely moving final pages, “Laudate eum in cymbalis benesonantibus . . . ,” are another manifestation of that same spiritual reserve.

Stravinsky is much concerned with unity. The psalms he chose are unified textually. The 39th Psalm is like an answer to the 38th. The “Alleluia” with which the 150th begins is the “new canticle” of the 39th. In another sense the Symphony is unified in that its three movements are linked and to be sung and played without pause. The first psalm ascends rapidly to its conclusion. With the first notes of the next psalm it becomes clear that the whole first movement has been one great upbeat to the second. Here is Stravinsky’s account of that second movement: “The ‘Waiting for the Lord’ Psalm makes the most overt use of musical symbolism in any of my music before The Flood. An upside-down pyramid of fugues, it begins with a purely instrumental fugue of limited compass and employs only solo instruments. . . . The next and higher stage of the upside‑down pyramid is the human fugue, which does not begin without instrumental help for the reason that I modified the structure as I composed and decided to overlap instruments and voices to give the material more development, but the human choir is heard a cappella after that. The human fugue also represents a higher level in the architectural symbolism by the fact that it expands into the bass register. The third stage, the upside‑down foundation, unites the two fugues [Et immisit in os meum canticum novum].”

Stravinsky regards Psalm 150 “as a song to be danced, as David danced before the ark.” He also startled many of his listeners and readers when Dialogues and a Diary (his book with Robert Craft) came out in 1963 with the statement that “the allegro in the 150th Psalm was inspired by a vision of Elijah’s chariot climbing the heavens [11 Kings 2, 11]; I do not think I had ever written anything so literal as the triplets for horns and piano to suggest the horses and the chariot. The final hymn of praise must be thought of as issuing from the skies; agitation is followed by the calm of praise.”

There is one more great crescendo as God is praised with timbrel and choir (Stravinsky does not take the Psalmist’s hints on orchestration), but for the praise on high-sounding cymbals and cymbals of joy, the music settles into timeless, motionless quiet. Great censers swing and quiet voices fill the air with their adoration. Or, in music, pianos, harps, and timpani move through three notes over and over, while in the same register as the voices, cellos and trumpets, later on oboes, finally all the winds, spread harmony at once rich and luminous. The “Alleluia,” the new canticle, returns for a moment to resolve, with the last “Dominum,” everything into a C major chord, severe and beatific, as beautiful and as special as only Stravinsky could make it. (Michael Steinberg)

San Francisco Symphony

Michael Tilson Thomas, conductor

San Francisco Symphony

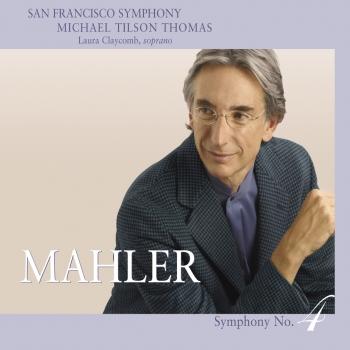

The San Francisco Symphony, widely considered to be among the most artistically adventurous and innovative arts institutions in the U.S., celebrated its Centennial season in 2011-12. The Orchestra was established by a group of San Francisco citizens, music-lovers, and musicians in the wake of the 1906 earthquake, and played its first concert on December 8, 1911. Almost immediately, the Symphony revitalized the city's cultural life. The Orchestra has grown in stature and acclaim under a succession of distinguished music directors: American composer Henry Hadley, Alfred Hertz (who had led the American premieres of Parsifal, Salome, and Der Rosenkavalier at the Metropolitan Opera), Basil Cameron, Issay Dobrowen, the legendary Pierre Monteux (who introduced the world to Le Sacre du printemps and Petrushka), Enrique Jordá, Josef Krips, Seiji Ozawa, Edo de Waart, Herbert Blomstedt (now Conductor Laureate), and current Music Director Michael Tilson Thomas (MTT). Led by Tilson Thomas, who begins his nineteenth season as Music Director in 2013-14, the SFS presents more than 220 concerts annually, and reaches an audience of nearly 600,000 in its home of Davies Symphony Hall, through its multifaceted education and community programs, and on national and international tours.

Since Tilson Thomas assumed his post as the SFS's eleventh Music Director in September 1995, he and the San Francisco Symphony have formed a musical partnership hailed as one of the most inspiring and successful in the country. His tenure with the Orchestra has been praised for outstanding musicianship, innovative programming, highlighting the works of American composers, and bringing new audiences to classical music. In addition, the Orchestra has been recognized nationally and internationally as a leader in music education and for the use of multimedia, television, technology, and the web to make classical music available worldwide to as many people as possible. MTT now is the longest-tenured music director for a major American orchestra, and the longest-serving music director in the San Francisco Symphony's history.

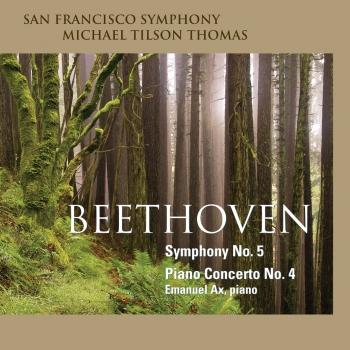

In its Centennial season, the Orchestra reprised its acclaimed American Mavericks Festival of music by pioneering modern American composers, featuring the world premieres of four commissioned works in two weeks of concerts at Davies Symphony Hall and on a two-week national tour, including four performances at Carnegie Hall. The San Francisco Symphony regularly mounts special weeklong semi-staged productions with multimedia, hosted and curated by MTT, and in 2012-13 presented specially staged performances of Grieg's Peer Gynt and the first concert performances by an orchestra of the complete music from Bernstein's West Side Story, which were recorded for release on SFS Media. Tilson Thomas and the Orchestra also dedicated several weeks to explorations of the music of Beethoven, selections of which were recorded for SFS Media, and Stravinsky, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the premiere of his Rite of Spring.

Since 1996, when Tilson Thomas led the Orchestra on the first of their more than a dozen national tours together, they have continued an ambitious yearly touring schedule that takes them to Europe, Asia and throughout the United States. In March 2014 they return to Europe for a three-week tour performing repertoire from the SFS Media catalogue including John Adams' Absolute Jest, Ives' A Concord Symphony, Mahler's Symphony No. 3, and Berlioz' Symphonie fantastique at two concerts each in London, Paris, and Vienna, and performances in Prague, Geneva, Luxembourg, Dortmund, and Birmingham. In 2012, they performed during a two-week national American Mavericks tour and a two-week tour of Asia with pianist Yuja Wang in Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Tokyo, Taipei, and Macau. In 2011, they made a three-week tour of Europe, culminating in Vienna performances of three Mahler symphonies to commemorate the anniversaries of the composer's birth and death. Recent touring highlights also include a three-week 2007 European tour that featured two televised appearances at the BBC Proms in London and concerts at several other major European festivals.

The Orchestra's recording series on SFS Media continues to reflect the artistic identity of its programming, including its commitment to performing the work of American maverick composers alongside that of the core classical masterworks. The San Francisco Symphony has recorded works from the American Mavericks Festival

concerts by Henry Cowell, Lou Harrison, and Edgard Varèse with pianist Jeremy Denk and organist Paul Jacobs, and won a 2013 Best Orchestral Performance Grammy award for its recording of John Adams' Harmonielehre and Short Ride in a Fast Machine. Other recently recorded works include Beethoven's Symphonies No. 5, 7, 9, and Piano Concerto No. 4, with soloist Emanuel Ax; Ives' A Concord Symphony; and Copland's Organ Symphony with Paul Jacobs. A live performance of John Adams' Absolute Jest with the St. Lawrence String Quartet and the Orchestra was recorded for future release on SFS Media, and live performances of Beethoven's Symphony No. 2 and Cantata on the Death of Emperor Joseph II was released in November 2013. Tilson Thomas and the Orchestra have recorded all nine of Gustav Mahler's symphonies and the Adagio from the unfinished Symphony No. 10, and the composer's works for voices, chorus, and orchestra for SFS Media. Their 2009 recording with the SFS Chorus of Mahler's sweeping Symphony No. 8, Symphony of a Thousand, and the Adagio from Symphony No. 10 won three Grammy awards, including Best Classical Album and Best Choral Performance. Other significant recordings include scenes from Prokofiev's Romeo and Juliet, a collection of Stravinsky ballets, a Gershwin collection, and Charles Ives: An American Journey, among others. In addition to fifteen Grammy awards, seven of them for the Mahler cycle, the SFS has won some of the world's most prestigious recording awards, including Japan's Record Academy Award, France's Grand Prix du Disque, and Germany's ECHO Klassik Award.

Tilson Thomas and the SFS launched the national Keeping Score PBS television series and multimedia project in 2006 to help make classical music more accessible to people of all ages and musical backgrounds. The project, an unprecedented undertaking among orchestras, is anchored by eight composer documentaries, hosted by Tilson Thomas, and eight live concert films; it also includes www.keepingscore.org, an innovative website to explore and learn about music; a national radio series; documentary and live performance DVD and CDs; and an education program for K-12 schools to further teaching through the arts by integrating classical music into core subjects. More than six million people have seen the Keeping Score television series, and the radio series has been broadcast on almost 100 stations nationally.

The San Francisco Symphony provides the most extensive education programs offered by any American orchestra today. In 1988, the Symphony established Adventures in Music (AIM), a free, comprehensive music education program that reaches every first- through fifth-grade child in the San Francisco Unified School District. The SFS Instrument Training and Support program reaches students in all San Francisco public middle and high schools with instrumental music programs, providing coaching by professional musicians. The Symphony expanded its educational offerings in 2011-12 with Community of Music Makers, a program that supports amateur choral singers and instrumental musicians with professional coaching by SFS musicians, rehearsals, and other learning opportunities. In development is a revitalized children's music education website, www.sfskids.org, created in conjunction with the UC Irvine Center for Computer Games and Virtual Worlds. The SFS also offers opportunities to hear and learn about great music through its programs Concerts for Kids, Music for Families, the internationally-acclaimed SFS Youth Orchestra, and annual free and community concerts.

This album contains no booklet.