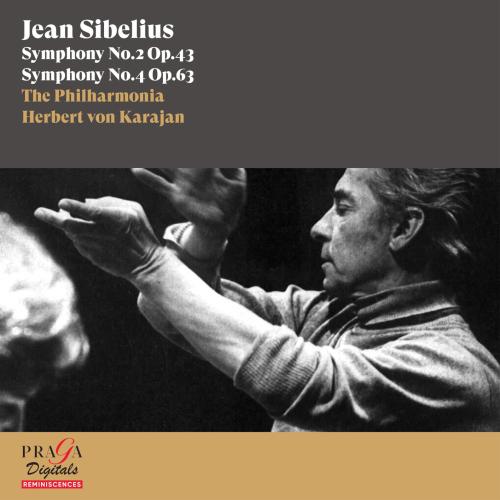

Jean Sibelius: Symphonies No. 2 & No. 4 (Remastered) The Philharmonia & Herbert von Karajan

Album info

Album-Release:

2022

HRA-Release:

13.04.2022

Label: Praga Digitals

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Orchestral

Artist: The Philharmonia & Herbert von Karajan

Composer: Jean Sibelius (1865-1957)

Album including Album cover Booklet (PDF)

- Jean Sibelius (1865 – 1957): Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 43:

- 1 Sibelius: Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 43: I. Allegretto 09:29

- 2 Sibelius: Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 43: II. Tempo andante, ma rubato - Andante sostenuto - Allegro - Andante sostenuto 13:44

- 3 Sibelius: Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 43: III. Vivacissimo - Lento e suave - Tempo I 06:47

- 4 Sibelius: Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 43: IV. Finale. Allegro moderato 13:46

- Symphony No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 63:

- 5 Sibelius: Symphony No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 63: I. Tempo molto moderato, quasi adagio - Adagio - Tempo I - Adagio - Tempo I 09:43

- 6 Sibelius: Symphony No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 63: II. Allegro molto vivace 04:59

- 7 Sibelius: Symphony No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 63: III. Il tempo largo 12:03

- 8 Sibelius: Symphony No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 63: IV. Allegro 09:22

Info for Jean Sibelius: Symphonies No. 2 & No. 4 (Remastered)

Two classic recordings by Karajan while he was in London as the imposed guest of Walter Legge, director of the Philharmonia Orchestra. The two symphonies form a lavish but unusual combination – Symphony no.2, the most popular of the seven created the composer of Valse Triste, and his curious Symphony no.4, a violent, arid, anti- Malherian dissertation infused with doubt and melancholy due to its baleful (augmented fourth) tritone interval, the hitherto spurned diabolus in musica. Two paradoxal masterworks.

Nowadays, in an age where there is a glut of Sibelius recordings to choose from, it’s easy to forget that Karajan was flying the flag for the composer at a time when his music was largely ignored outside of Finland, the UK and America. This release is a timely reminder of the excellence of the conductor’s early work with the Philharmonia Orchestra and it’s good to welcome these historic recordings back into circulation.

"There is a striking similarity between the two earlier versions. Sibelius himself was an admirer of the Philharmonia recording. It is certainly the coldest and most desolate of the 3 Karajans on offer. The first movement also has an underlying menace matched by no other conductor. Allowances have to be made for the 1953 mono recording but it is beautifully balanced and the Philharmonia strings are sonorous and dark. The ear quickly adjusts to the lean, dry sound. This is a tough, intense reading that is well worth hearing. There is, however, something for the potential purchaser to consider. These performances, in what to my ears sound like equally good transfers ..." (John Whitmore, MusicWeb International)

Philharmonia Orchestra

Herbert von Karajan, conductor

Digitally remastered

Herbert von Karajan

Karajan’s father was a doctor at the Salzburg hospital and his mother was of Slav descent. He began to take piano lessons when he was four, and studied chamber music, composition, piano and theory at the Salzburg Mozarteum for ten years from 1916. His tutors included Bernhard Paumgartner, who conducted his first concerto appearance in 1919 and encouraged him to become a conductor. After graduating from the Mozarteum in 1926, Karajan entered the Vienna Academy, where he studied piano with Hofmann and conducting with Wunderer. At the beginning of 1929 he conducted the Salzburg Mozarteum Orchestra; as a result he was offered the chance to conduct a trial performance by the director of the Ulm Municipal Theatre, and subsequently was appointed as chief conductor, a post he held from 1929 to 1934. During this period he also conducted the Vienna Symphony Orchestra and joined the Nazi party not once but twice, in Ulm and also in Aachen, where from 1934 to 1942 he was chief conductor, conducting both opera and symphony concerts. He made his debut at the Vienna State Opera in 1937 conducting Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde and during the following year appeared with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. After performances of Beethoven’s Fidelio and Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde at the Berlin State Opera he was hailed as ‘Der Wunder Karajan’ (‘The Karajan Miracle’) by the Berlin music critic von der Nüll, and was offered a recording contract by Deutsche Grammophon; in 1939 he was appointed as ‘state conductor’ at the Berlin Staatsoper and as conductor of the Staatsoper orchestra’s symphony concerts.

During most of World War II Karajan was active in Berlin and in certain occupied and friendly territories such as France and Italy and was seen as a potent rival to Furtwängler, then at the head of the Berlin Philharmonic; but as the war drew to a close he fled from Germany and lived primarily in Italy. Because of his membership of the Nazi party Karajan was not permitted to conduct in public in Vienna after hostilities had ceased, but he was allowed to record for Walter Legge and the British Columbia label. The ban on conducting was lifted in 1947, and during the following year he was appointed as chief conductor of the Vienna Symphony Orchestra and of the Vienna Musikverein Choral Society, began to work as the de facto chief conductor of Legge’s Philharmonia Orchestra, and appeared at the Salzburg Festival and La Scala, Milan. In addition he accepted many guest engagements in Austria, England, Germany, Italy and Switzerland.

By the beginning of the 1950s Karajan’s star was definitely once again in the ascendant. At the first post-war Bayreuth Festival, held in 1951, he conducted both Wagner’s Ring and Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, followed the next year by an incandescent interpretation of Tristan und Isolde. His numerous recordings for Legge established and confirmed his international reputation through their undeniable quality. Following the death of Furtwängler at the end of 1954 Karajan was appointed as chief conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, a post which he was to hold until 1989, touring internationally with the orchestra from 1957 onwards. Next he was appointed as artistic director of the Salzburg Festival, from 1956 to 1960, and of the Vienna State Opera, from 1957 to 1964. Here he promoted co-operation with La Scala, and sought to introduce the Italian stagione system in place of the traditional repertoire system with its concomitant difficulties with rehearsals. In 1959 Deutsche Grammophon signed a long-term recording contract with Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, the significance of which cannot be over-estimated in terms of generating reputation and income. At one point recordings by Karajan constituted twenty-five percent of the label’s classical catalogue, and during his lifetime more than one hundred million copies of his recordings were sold world-wide.

The new concert hall in West Berlin, the Philharmonie, was inaugurated by Karajan in 1963, and the following year he joined the board of directors of the Salzburg Festival, where he exerted considerable influence. In 1967 he established the Salzburg Easter Festival with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra as resident, and inaugurated it with his own production of Die Walküre, which was shared with the Metropolitan Opera in New York; the Salzburg Whitsun Concerts followed in 1973. He founded the Karajan Foundation in Berlin in 1968, a significant legacy of which was a conducting competition which helped to identify the major conductors of the following generation. Between 1969 and 1971 Karajan acted as musical counsellor for the Orchestre de Paris, created to replace the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra. In 1978, the year in which he was awarded an honorary doctorate by Oxford University, he suffered a severe fall which was to affect his mobility for the rest of his life. He conducted the traditional New Year’s Day concert with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra in 1987, and his eightieth birthday was marked in 1988 by Deutsche Grammophon with the issue of a one hundred-CD Karajan Edition. He died of heart failure the following year while preparing Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera for the Salzburg Festival.

Karajan was an extraordinary conductor, who possessed an unusually high degree of personal charisma which was almost tangible when experienced directly in the concert hall and opera house. He often conducted with his eyes closed, generating a high level of concentration and tension, and was able to exact performances of remarkable technical accuracy and control from his orchestras. He combined these traits with a love of the smoothest legato and subtlest phrasing. Taken all together these characteristics could result in slightly ‘soft-centered’ or mannered performances. His discography was vast: towards the end of his life his recordings, generally made under his own control, were auctioned to EMI and Decca as well as to Deutsche Grammophon, thus furthering their international distribution. Karajan is perhaps best experienced in the repertoire by which he was most popularly known, the Viennese classics, such as the symphonies of Beethoven, Brahms and Bruckner. A relatively late convert to Mahler, he was nonetheless an impressive interpreter of this elusive composer. His operatic recordings, especially those made with Walter Legge for EMI, are of a very high quality. A keen supporter of technological innovation, he allied himself closely to the introduction of the compact disc, first unveiled to the public in 1981, and to digital recording. He also recorded opera and concerts on film, with himself conducting, from 1965 onwards, and so has left an impressive visual musical legacy which has subsequently been made available on DVD.

Booklet for Jean Sibelius: Symphonies No. 2 & No. 4 (Remastered)