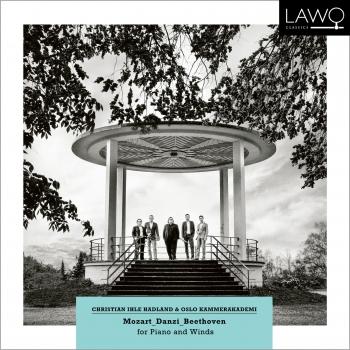

Mozart / Danzi / Beethoven: for Piano and Winds Christian Ihle Hadland

Album info

Album-Release:

2019

HRA-Release:

15.11.2019

Label: Lawo Classics

Genre: Classical

Artist: Christian Ihle Hadland

Composer: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756 –1791), Franz Danzi (1763-1826), Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

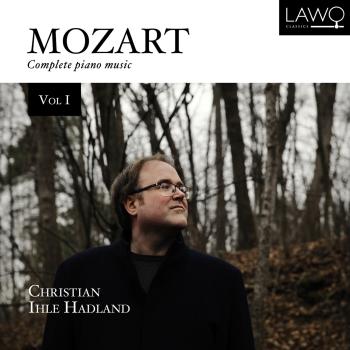

Album including Album cover

I`m sorry!

Dear HIGHRESAUDIO Visitor,

due to territorial constraints and also different releases dates in each country you currently can`t purchase this album. We are updating our release dates twice a week. So, please feel free to check from time-to-time, if the album is available for your country.

We suggest, that you bookmark the album and use our Short List function.

Thank you for your understanding and patience.

Yours sincerely, HIGHRESAUDIO

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756 - 1791): Quintet in E-flat major, KV 452:

- 1 Quintet in E-flat major, KV 452: I. Largo - Allegro moderato 10:04

- 2 Quintet in E-flat major, KV 452: II. Larghetto 07:47

- 3 Quintet in E-flat major, KV 452: III. Allegretto 05:42

- Franz Ignaz Danzi (1763 - 1826): Quintet in D minor, Op. 41:

- 4 Quintet in D minor, Op. 41: I. Larghetto - Allegro 12:29

- 5 Quintet in D minor, Op. 41: II. Andante sostenuto 08:57

- 6 Quintet in D minor, Op. 41: III. Allegretto 04:48

- Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 - 1827): Quintet in E-flat major, Op. 16:

- 7 Quintet in E-flat major, Op. 16: I. Grave - Allegro ma non troppo 13:07

- 8 Quintet in E-flat major, Op. 16: II. Andante cantabile 07:01

- 9 Quintet in E-flat major, Op. 16: III. Rondo - Allegro, ma non troppo 05:46

Info for Mozart / Danzi / Beethoven: for Piano and Winds

During their first 10 years, the Oslo Kammerakademi has released a number of acclaimed recordings on the LAWO Classics label, and in this,

their anniversary year - along with pianist Christian Ihle Hadland - offer some extra special treats for piano and winds!

W.A. Mozart wrote the following in a letter to his father on April 10, 1784 about his Quintet in E-flat major, KV 452 for piano and four winds: “I hold it to be the best work I have ever written.” At this time, Mozart was already a celebrated composer with more than 450 works to his name. Not surprisingly, Mozart writes fantastically well for piano. He also writes completely idiomatically for winds; perhaps no composer, before or since, has brought forth the voice of each individual wind instrument in the same way as Mozart.

Composing quintets for this instrumentation in the wake of Mozart’s pioneering work couldn’t have been an easy task, but after all Danzi came from Mannheim, where Mozart a few years earlier had become acquainted with the city’s renowned court orchestra, which in itself was pioneering. The orchestra was known, among other things, for using the winds to a much greater soloistic extent than what was considered the norm in Mozart’s hometown of Salzburg. Danzi’s biggest accomplishment as a composer was his ability to place winds on the map for a large number of chamber music works.

Beethoven’s quintet makes clear references to Mozart’s trailblazing work for this instrumentation. He chooses the same key, and the work possesses the same external structure as Mozart’s, but the content is completely different. Beethoven displays an emotional depth whereas Mozart sets himself on a divergent track - Beethoven offers surprises and unforeseen whims, while Mozart chooses to be gallant and poised.

Christian Ihle Hadland and Oslo Kammerakademi exhibit their distinctive signature on this CD - virtuosic and passionate playing combined with historical performance practice, alongside modern and historical instruments, in beautiful unity. Christian Ihle Hadland has established himself amongst the European elite as a soloist and chamber musician. Critics have called attention to Hadland’s broad diversity in his treatment of sound, subtle phrasing, and singing tone. Oslo Kammerakademi performs chamber music for winds with the historical Harmoniemusik instrumentation as a foundation. Founded by Artistic Director and oboist David Friedemann Strunck, the ensemble has established itself as a leader in Europe, with critically acclaimed CD recordings and recurring invitations to prestigious festivals. Oslo Kammerakademi utilizes historical brass instruments in repertoire from the baroque, classical, and romantic periods.

About the album: Unfortunately there is no real Norwegian language equivalent to the expression “unsung hero,” but one can immediately place Franz Danzi in that category. His upbringing in Mannheim in the 1770s and 80s provided him with the perfect backdrop to experience the most important musical currents of the time, where people puttered around with such things as synchronized bowings and soloistic wind parts in the orchestra – elements commonplace to us today, but considered quite groundbreaking then. The young Danzi also met Mozart, who showed a great interest in the pioneering work in Mannheim, and Danzi expressed boundless admiration for the old master throughout his entire life.

Danzi’s big dream was to further develop the German Singspiel genre, where Mozart, with the operas The Abduction from the Seraglio and The Magic Flute, had laid a golden foundation. Danzi’s wife, Margarethe Marchand, was an outstanding soprano and an enthusiastic promoter of her husband’s works, but when she died at the young age of 32, Danzi seemed to lose interest in the genre. However, he was an avid supporter and inspiration to his younger colleague, Carl Maria von Weber. Weber’s Singspiel Der Freischütz (The Marksman) took the genre to new heights, with the manifestation of nature as a singing creature. For this we must

thank Danzi!

Quintets for winds and piano are a rare bird in music history, and the reason for that may very well be that Mozart’s and Beethoven’s own works set such high standards that few dared to follow in their footsteps. This idea is by no means an oddity. We can think of the clarinet quintets of Mozart and Brahms, which depict a perfectly symbiotic soundscape just waiting to be explored. But where these two towers loom over all others, later “structures” have been few and far between. From the Mannheim development, which gave the winds more space in the orchestra, came the desire for pure wind ensembles of various sizes, and also in combination with other instruments. Mozart’s quintet is a natural first stopping point for this development, and as is often the case with Mozart, his first attempt becomes a great success: an ensemble that basically isn’t particularly homogenous, in a perfect unit, where there is still plenty of room for each instrument to shine. The piano has a supporting role but often discreetly lies in the background against the vibrant escapades of the winds. The first movement has a lithe introduction where the lines wander, in the most outstanding Mozart-esque way, from instrument to instrument, intersecting and inspiring each other, but never overshadowing or disturbing one another. The Larghetto is an archetypal Mozart movement from this period, seemingly uncomplicated, but where long, increasingly intricate harmonic surfaces unfold before it all returns to the charming, operatic bits that bring us safely to shore. And to mark the soloistic element of this quintet, Mozart rounds off the finale’s lively rondo with a brief cadenza, where the instruments mimic each other before uniting together toward the final stretch.

One of music history’s most mythical, yet almost unwritten encounters is the one that took place between Mozart and the then 16-year-old Beethoven in Vienna in 1787. Virtually every source contradicts the other. Some claim that Mozart was beside himself with enthusiasm, others that he was lukewarm and didn’t want Beethoven as his student. Neither Mozart nor Beethoven mentions the meeting in his own correspondence, but we can infer from Beethoven’s late sketchbooks he used to keep a conversation going – he received written questions and answered them verbally – that a meeting took place and that there may have been more than just cordiality on Mozart’s part.

Mozart was 28 years old when he composed his quintet. With over 450 works under his belt, his name was well-established in Vienna and he could thus allow himself to compose a piece where other musicians could shine. Beethoven was a relatively unknown 26-year-old when he released his quintet. He first and foremost sought to emerge as a pianist, and to a lesser extent a composer. His quintet is often regarded as a twin piece to Mozart’s, but despite all the external similarities – the key, the slow introduction, the three movements – they have very little else in common. Mozart represents the coronation of classicism, an Olympic, brilliantly clarified form in which established frames are fully exploited. Beethoven wants to get away from white, delicate porcelain skin under parasols in the imperial pavilions into a raw world where the pianist is quite impolite as the work draws to a close, leaving on a long improvisational tour while the other musicians find themselves sitting and waiting. The theme continues when it suits him. Still, there is no doubt that Beethoven’s quintet is very much an ensemble piece; the twisted evolution of ideas in the first movement’s introduction and the mysterious, veiled development section in that same movement is the work of a master. Long, swimming pedals and a canon section in the finale, that most of all sounds like a big misunderstanding, are both indicative of what’s to come. Early Beethoven has an uncomplicated, musical feel, the welcoming and charming themes of the 2nd and 3rd movements sit in one’s ear and both form the basis for the rondo movements with delicately carved, contrasting episodes.

As a liberating antithesis to the happiness in E-flat, comes Danzi’s quintet in D minor. Here we are far from lace and crystal, but on the contrary, deep-seated in a pre-romantic, bleak landscape – and perhaps the slow introduction is a slight nod to Mozart’s unfinished requiem? To a greater extent than Beethoven, Danzi sets the piano and winds up against each other, where themes are often first presented in the winds and are then embroidered or further developed in the piano voice – which in the first movement is swirling and swarming, while the wind voice is heavy, broad, and insistent. The second movement begins with a gentle, slightly withdrawn theme before it all slowly rolls away, seasoned with improvisational whims and long, uninterrupted sounds. The third movement is an abrupt affair with a partly jarring, somewhat singable theme, interrupted by more optimistic middle parts, which nevertheless fail to remove the impression of a rather dark world.

All in all, a trilogy of vastly different origins takes shape – the superb Mozart, the forging ahead, self-centered Beethoven, and the “worker ant” Danzi, who while playing the piano himself, wanted to clear a space for wind instruments within chamber music. He achieved this not in the least as the “father” of the wind quintet, where he has a catalogue of outstanding works to his name. – Christian Ihle Hadland

Christian Ihle Hadland, piano

Oslo Kammerakademi

Christian Ihle Hadland

has, over the past decade, established himself as one of Norway’s leading pianists and a true craftsman of his instrument. Known for his refined touch, musical sensitivity, and deep interpretive insight, he is equally at home in solo, concerto, and chamber settings. His delicate and intelligent approach has made him a sought-after artist on some of the world’s most prestigious stages.

Born in Stavanger in 1983, Christian Ihle Hadland began playing the piano at the age of eight and showed early promise. At eleven, Christian was admitted to the Rogaland Music Conservatory, and in 1999 he began studies with the renowned teacher Jiří Hlinka, both privately and at the Barratt Due Institute of Music in Oslo. This strong foundation led to his professional concerto debut at the age of fifteen with the Norwegian Radio Orchestra (KORK).

In 2011, Christian came to international attention as a BBC New Generation Artist, a prestigious scheme that supports emerging talents. During his two-year tenure, he performed with all five BBC orchestras across the UK and gave a series of solo and chamber recitals broadcast by the BBC. He concluded this residency with a major highlight: performing Beethoven’s Second Piano Concerto with the Oslo Philharmonic under Vasily Petrenko at the BBC Proms, where his playing was praised for its “pearly” tone and “otherworldly” expressiveness by the London press.

Christian has appeared as a concerto soloist with all the major orchestras in Scandinavia, including the Oslo Philharmonic, the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, the Danish National Symphony Orchestra, the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, and the Helsinki Philharmonic. In the UK, he has performed with the Hallé Orchestra, the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Manchester Camerata, and several BBC ensembles. Recent international engagements include his debut with the Orchestre National de Lyon under Leonard Slatkin, a return to the Helsinki Philharmonic with Thomas Søndergård, and concerts with the BBC Philharmonic and the Norwegian Chamber Orchestra. His appearances in France, Germany, and Japan have also been widely praised.

A highly respected chamber musician, Christian is the Artistic Director of the International Chamber Music Festival in Stavanger, a position he has held since 2010. He is a frequent guest at Wigmore Hall, where he made his solo debut in 2013, and is a regular artist at the Bergen International Festival. He has also performed at the BBC Proms Chamber Music Series, collaborating with ensembles like the Signum Quartet. His chamber partners include Susan Graham, with whom he toured Australia in 2015 alongside the Australian Chamber Orchestra, and Renée Fleming, with whom he performed at the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony in 2006.

Christian Ihle Hadland’s discography is rich and diverse. His recording of Mozart piano concertos with the Oslo Philharmonic was nominated for a Spellemann Prize, Norway’s top recording award. He won the prize in 2015 with Holberg Variations, recorded with Ensemble 1B1. His collaboration with cellist Andreas Brantelid on a disc of works by Grieg and Grainger (BIS) was chosen as a Gramophone Editor’s Choice. Other recent highlights include The Lark (Simax), nominated for the 2017 Spellemann Prize, and Nordic Rhapsody with violinist Johan Dalene, showcasing music from across the Nordic countries.

Christian Ihle Hadland has collaborated with many of the world’s finest conductors, including Sir Andrew Davis, Herbert Blomstedt, and Thomas Dausgaard. He continues to perform across Europe and beyond, earning acclaim for his poetic sound, stylistic integrity, and deep musical understanding.

Whether in the concert hall, recording studio, or chamber setting, Christian Ihle Hadland brings a thoughtful, human quality to every performance, confirming his place as one of the most gifted and versatile pianists of his generation.

This album contains no booklet.