Mahler: Symphony No. 8 Berliner Philharmoniker & Sir Simon Rattle

Album info

Album-Release:

2020

HRA-Release:

27.08.2021

Label: Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Vocal

Artist: Berliner Philharmoniker & Sir Simon Rattle

Composer: Gustav Mahler (1860 – 1911)

Album including Album cover Booklet (PDF)

- Gustav Mahler (1860 - 1911): Symphony No. 8, Erster Teil:

- 1 Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Erster Teil: I. Veni, creator spiritus 05:49

- 2 Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Erster Teil: II. Infirma nostri corporis 11:29

- 3 Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Erster Teil: III. Veni, creator spiritus 04:07

- 4 Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Erster Teil: IV. Gloria Patri Domino 02:27

- Symphony No. 8, Zweiter Teil:

- 5 Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Zweiter Teil: V. Poco adagio 09:40

- 6 Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Zweiter Teil: VI. Waldung, sie schwankt heran 04:27

- 7 Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Zweiter Teil: VII. Ewiger Wonnebrand 01:41

- 8 Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Zweiter Teil: VIII. Wie Felsenabgrund mir zu Füßen 04:25

- 9 Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Zweiter Teil: IX. Gerettet ist das edle Glied der Geisterwelt vom Bösen 03:02

- 10 Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Zweiter Teil: X. Uns bleibt ein Erdenrest 03:04

- 11 Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Zweiter Teil: XI. Höchste Herrscherin der Welt! 07:15

- 12 Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Zweiter Teil: XII. Bei der Liebe, die den Füßen 04:42

- 13 Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Zweiter Teil: XIII. Neige, neige, du Ohnegleiche 05:02

- 14 Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Zweiter Teil: XIV. Blicket auf zum Retterblick 05:36

- 15 Mahler: Symphony No. 8, Zweiter Teil: XV. Alles Vergängliche ist nur ein Gleichnis 05:32

Info for Mahler: Symphony No. 8

“Forewords” to the Eighth

When Simon Rattle prefaced his interpretation of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony with Henry Purcell’s Funeral Music, he was seeking programmatic unity through the idea of the funeral march. Introducing this performance of the Eighth Symphony are liturgical settings from the Renaissance and Baroque, polychoral works of the old masters that prefigure the conception of a “resounding universe” by which Mahler described his newly completed Eighth. The ultimate example of this style is the Tudor court organist Thomas Tallis’s 40-part motet Spem in alium. An essential feature of this composition’s structure is the alternation between imitative passages involving only a few voices and huge tutti entries with powerful chords.

The idea of a polyphonic overlay of vocal lines also inspired Antonio Lotti 150 years later. Born in Hanover, he lived most of his life in Venice, where he served as organist and later maestro di cappella at St. Mark’s. Among his compositions for the basilica are a number of highly expressive settings of the Crucifixus for 5-10 voices, the manuscripts of which are still widely scattered in libraries in Europe and the US. In place of the almost cosmically revolving consonances in the Tallis motet, Lotti’s eight-part Crucifixus features the expressive dissonances of the Italian Baroque known as durezze.

“My most important work” – Gustav Mahler’s Eighth Symphony

“It would be absurd if my most important work happened to be the easiest to understand,” wrote Mahler to his wife Alma in September 1909 after playing portions of his Eighth Symphony to his Dutch friends Willem Mengelberg and Alphons Diepenbrock. “It’s funny: the work always makes the same, typically powerful impression.” These were harbingers of the overpowering effect the Eighth would make at its world premiere in Munich’s Neue Festhalle on 12 September 1910. All the more rapid was the decline of its reputation in later decades when Theodor W. Adorno’s polemical phrase “giant symbolic shell” made the rounds. It was not the only objection raised against this exceptional work. One saw in its affirmative tone a retreat from the scepticism of the three preceding instrumental symphonies. Mahler biographer Jens Malte Fischer has declared: “The Eighth was reproached for having committed itself too wholeheartedly to the late 19th-century’s appetite for the value-producing, value-celebrating Gesamtkunstwerk in an age of the value vacuum.”

The composer would have been baffled by such reservations, convinced as he was that the Eighth was a gift from above. In a letter to Alma he recalled beginning work on the symphony in June 1906: “Four years ago, on the first day of the holidays, I went up to my hut at Maiernigg with the firm resolution of idling the holiday away ... and recruiting my strength. On the threshold of my old workshop the spiritus creator took hold of me and shook me and drove me on for the next eight weeks until my greatest work was done.”

Mahler himself helped weave the legend of that euphoric summer of 1906. He reportedly found the Pentecost hymn Veni Creator Spiritus by the 9th-century Mainz archbishop Hrabanus Maurus in a “damned old hymnbook”. When the “creative spirit took hold” of him, there was no room for textual questions. Only later did he discover that two and a half strophes of the original were missing from his popular version of the hymn, but, miraculously, they fit seamlessly into the sketches he had drafted without knowledge of this additional text. So it was that one thing after another contributed to the notion that this work in its entirety was meant to be.

Veni Creator Spiritus

Mahler set the Whitsun hymn as a powerful symphony cantata for double chorus, boys choir and orchestra, tonally centred in the typical hymn key of E flat major and organized in a taut sonata form, whose themes recur and are transformed in the symphony’s second part. In the middle of the first part’s development, a powerful new theme is introduced that symbolizes the text “Accende lumen sensibus”: “Illuminate our senses”. It is this theme that begins Part II, now in E flat minor and moved down to the basses in muffled pizzicato to depict Goethe’s “mountain gorge”. In the course of the second part, the theme recovers its euphoric power as a symbol of creativity itself, which Mahler in this symphony connects with the theme of Eros, redeeming love. At the end of the work, the Eternal Feminine that “leads us on high” and the descending Creative Spirit come together in a mystical union where the two forces are conformed and fused.

Scene from Faust

“We experience the truth of life without knowing how.” In this succinct phrase Goethe encapsulates what he is trying to say with the conclusion of Faust II. Mahler, too, was inspired by this idea when he set Goethe’s verses: Everything is revealed here through music – the ascent to the heights and disclosure of life’s ultimate truths – as the composer’s reply to the creativity kindled by the spirit in the first part. “Everything subjectively tragic is abolished in the Eighth,” he told Mengelberg. “Try to imagine the whole universe beginning to ring and resound. These are no longer human voices, but planets and suns revolving.”

The Eighth is also monumental in the sense that Mahler needed every musical element – from the six flutes to the elaborate choral sub-division – in order to particularize the various stages of Goethe’s ascent to the heights and, at the end, to reintegrate them in a grand conclusion. The scene begins with a long orchestral prelude, evoking the mountain gorge whose caves are home to the Anchorites, hermits of the early Church. From deep pizzicato basses in dark E flat minor, the view opens upward to where a keening woodwind theme floats in the strings’ tremolo clouds. This is the dotted-rhythm motif that informs all the love themes of this vast scene. Thus the orchestral prelude, both in its motifs and its strict counterpoint, prepares the “great liturgy”, as the final scene has been described.

For the Anchorites’ entry Mahler again takes up the double-chorus principle he uses in Part I, here as a division into tenors and basses singing, extremely softly and in alternation, “Waldung, sie schwankt heran” (“Wavering woods”) on clipped breathlike syllables – a visionary modern choral technique. The next big choral section leads us to “higher spheres”. It is the Chorus of Angels “carrying the immortal part of Faust”. Their verse “Gerettet ist das edle Glied der Geisterwelt vom Bösen” (“Now that precious part of our spirit world is saved from evil”) is sung at first by both women’s choirs together. Above them is the Chorus of Blessed Boys “circling round the highest peak”. Later the women’s voices are sub-divided: Mahler gives the Chorus of Younger Angels to the “lighter voices” of the first choir, that of the “More Perfect Angels” to the second women’s choir, further divided into sections. Doctor Marianus’s rapturous solo with chorus follows. Then the Boys intone “Er überwächst uns schon” (“He is already surpassing us”), the choral sound growing ever more ecstatic and splendid until it culminates in “Jungfrau, Mutter, Königin, Göttin, bleibe gnädig!” (“Virgin, Mother, Queen, Goddess, keep us in thy favour”). Following a numinous orchestral interlude the nearly hour-long movement reaches its final consummation in the “Chorus mysticus”: “All that passes away is only a likeness”. The chorus’s ppp E flat major entry inevitably recalls “Auferstehen” (“Rise again”) at the end of the “Resurrection” Symphony. In a similarly broad, sweeping intensification – with the euphoric words “Blicket auf”, exhorting the penitents to “gaze aloft” at “her” saving glance, the work moves to its climax: “Das Ewig-Weibliche zieht uns hinan” (“The Eternal-Feminine leads us on high”). In the orchestral conclusion, the mighty “Veni creator” motif chimes in tellingly, welding the entire symphony into a gigantic unity. (Karl Böhmer)

Erika Sunnegårdh, Sopran

Susan Bullock, Sopran

Anna Prohaska, Sopran

Lilli Paasikivi, Mezzosopran

Nathalie Stutzmann, Alt

Johan Botha, Tenor

David Wilson-Johnson, Bariton

John Relyea, Bass

MDR-Rundfunkchor

Knaben des Staats- und Domchors Berlin

Rundfunkchor Berlin

Sir Simon Rattle, Dirigent

Berliner Philharmoniker

Beginnings

Spring 1882: When Benjamin Bilse announces the intention of taking his already underpaid orchestra on the train to Warsaw in fourth class for a concert, that's the last straw for 54 of his musicians. Calling themselves the 'former Bilse Kapelle', they decide to declare their independence. But at first the young ensemble has economic problems of its own to confront, and it isn't until the Berlin concert agent Hermann Wolff takes over its organization in 1887 that a stable basis for the future is finally established. He changes the name to 'Berliner Philharmonisches Orchester', turns a renovated roller-skating rink into the first 'Philharmonie' and seeks out the best conductors of the day for his musicians.

The great orchestral trainers

Hans von Bülow has already formed a first-class ensemble from his Meiningen Court Orchestra when he takes over the Berliner Philharmoniker. In only five years at the helm he lays the foundation of those special musical qualities that from now on will be indissolubly linked with the orchestra's name. Bülow's successors, on the other hand, come to stay. Arthur Nikisch, who takes up his post in 1895, goes on to influence the orchestra's style decisively for the next 27 years. He once writes: 'It can be asserted without hesitation that in a first-rate orchestral body every member deserves to be described as an 'artist',' and with this creed he encourages the Berlin musicians to develop a sense of themselves as 'soloists'. That quality still represents one of the Philharmonic's unmistakable trademarks.

When Nikisch dies in 1922, the orchestra unanimously chooses Wilhelm Furtwängler to succeed him. The young conductor builds on Nikisch's achievements. His idiosyncratic beat and his impassioned, inspired music-making demand from the musicians an extremely high level of autonomy and sensitivity. Furtwängler's philosophy emphasizes the timelessness of great works of art, and thus his greatest affinity is for the Classical and Romantic masters. He and his Berlin orchestra become legendary interpreters of the works of Beethoven, Brahms and Bruckner. At the same time Furtwängler expands the repertoire to include contemporary pieces by Schoenberg, Hindemith, Prokofiev and Stravinsky.

The turmoil of war

The National Socialist dictatorship and the war do irreparable damage to the German cultural landscape – including the Berliner Philharmoniker. The regime’s maniacal racial policy leads to the loss of valuable musicians, and the orchestra finds itself isolated from the international exchange of soloists and conductors. Meanwhile there is also an attempt to turn Germany’s representative ensemble into an instrument of official cultural politics. Nevertheless Furtwängler and the orchestra manage to salvage its artistic substance through the war.

But the comparatively rapid turnover of conductors in the early post-war period speaks for itself. The Philharmonic under Leo Borchard already gives its first concert on 26 May 1945 in the Titania-Palast, a converted cinema, but in August, through a tragic mistake, Borchard is shot and killed by an occupying soldier. Chosen to succeed him is a completely unknown young Romanian, virtually straight out of the Berlin Music Hochschule, where he has been studying. But the orchestra’s judgment proves itself to be acute: Sergiu Celibidache arouses great enthusiasm with his vivid personality and widely varied programmes until 1952, when the orchestra’s leadership is officially returned to the hands of Furtwängler. Also coming in the postwar period is the founding in 1949 of the “Gesellschaft der Freunde der Berliner Philharmonie e.V. ” (Society of Friends of the Berliner Philharmonie Inc.), which in subsequent decades sponsors the building of the new Philharmonie and continues to provide the hall with financial support.

The Karajan era

In November 1954 Wilhelm Furtwängler dies. The following April the Berliner Philharmoniker chooses as its artistic director the man who is to remain with the ensemble longer than any other - Herbert von Karajan. He works with the orchestra to cultivate a specific sound, an unprecedented perfection and virtuosity which lay the groundwork for the ensemble's national and international triumphs - both in the concert hall and through countless recordings.

Moreover, Karajan is able to expand the orchestra's activities in a number of new directions. With the founding of the Salzburg Easter Festival in 1967 the orchestra now has its own major international festival and an opportunity to make its mark as an opera orchestra. A further initiative is the Orchestra Academy of the Berliner Philharmoniker (Orchester-Akademie der Berliner Philharmoniker), in which young and talented instrumentalists are trained through practical experience to meet the stringent demands of a top-flight orchestra. The construction of the new Philharmonie also takes place during the Karajan era. Since October 1963 the orchestra has made its home in the concert hall designed by Hans Scharoun, (to which a chamber music hall is added in 1987).

Claudio Abbado

Herbert von Karajan died in July 1989, after nearly 35 years as the orchestra's artistic director. His successor was a familiar face. Claudio Abbado conducted the Philharmoniker for the first time in 1966 and earned the musicians' highest esteem during the intervening years. He was not an orchestral trainer in the manner of his predecessors but led through the sheer force of his conviction and artistic presence.

Abbado's programmes brought a pronounced shift in emphasis. Each cycle of concerts was given a thematic focus – for example, 'Faust', 'The Wanderer' or 'Music is Fun for All'. This conceptual modernisation corresponded to a significant rejuvenation of the Philharmoniker themselves. Well over half of the current membership joined the orchestra during this time. In February 1998 Claudio Abbado announced that he would not renew his contract beyond the 2001/2002 season, and in June of the following year the Berliner Philharmoniker elected a new chief conductor by a wide majority.

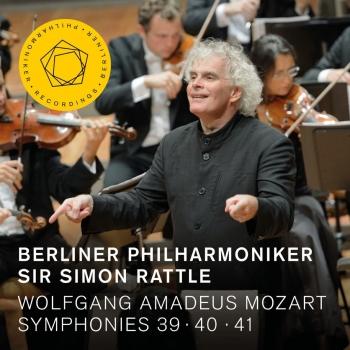

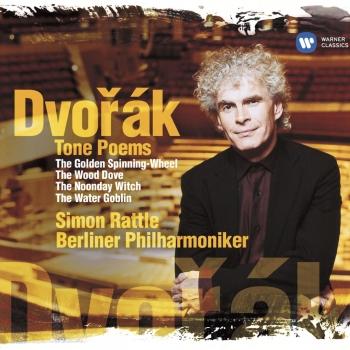

Sir Simon Rattle

With Sir Simon Rattle's appointment, the orchestra not only succeeded in recruiting one of the most talented conductors of the younger generation but also in introducing a series of important innovations. The conversion of the orchestra into a public foundation, the Stiftung Berliner Philharmoniker, on 1 January 2002 has provided a modern structure which allows a broad range of opportunities for creative development while ensuring the ensemble's economic viability. The foundation enjoys the generous support of the Deutsche Bank, its principal sponsor. One focus of this sponsorship is the education programme established when Sir Simon Rattle assumed his post and through which the orchestra addresses a broad public – young people in particular. Sir Simon Rattle has summarised his intentions as follows: 'The education programme reminds us that music is no mere luxury, but instead a fundamental need. Music must be a vital and essential element in the life of each individual.' In the 130-year history of the Berliner Philharmoniker this represents an expansion of the orchestra's cultural mandate, one to which they are dedicating themselves with characteristic commitment.

For this commitment the Berliner Philharmoniker and their artistic director were appointed as international UNICEF Ambassadors, an honour conferred for the first time on an artistic ensemble. In June 2011 the Berliner Philharmoniker and Sir Simon Rattle received the Glashütte Original Music Festival Award for their educational programming and their role as a model for the programmes of other cultural institutions.

As a result of the Berliner Philharmoniker Foundation's desire to open up the Philharmonie to wider sections of the population and make it an attractive location during the day as well, two new concert formats were launched during the 2007/2008 season. During the free Lunchtime Concerts presented every Tuesday in the Foyer of the Philharmonie, outstanding chamber music works are performed by ensembles from the Berliner Philharmoniker, the city's universities and other Berlin orchestras. In the chamber music series Alla turca, artists from the Orient and Occident came together for cultural dialogue and introduced their music, exploring the historical and cultural differences of the two cultures. Beginning with the 2011/2012 season, Alla turca was expanded to Unterwegs (Underway), a new world music series developed and presented by Roger Willemsen. Together with their partner, the Deutsche Bank, the Berliner Philharmoniker initiated a forward-looking project in January 2009: the Digital Concert Hall. Concerts by the Berliner Philharmoniker can now be enjoyed live in the Internet and retrieved from the video archive of the Digital Concert Hall at any time.

In spring of 2012 the Berliner Philharmoniker appeared for the last time at the Salzburg Easter Festival. In 2013 the orchestra will launch its new Easter Festival in Baden-Baden, with four opera performances each year, symphonic concerts and a wide array of chamber music programmes. In addition, the orchestra will also devote itself particularly to encouraging young musicians and artists.

Booklet for Mahler: Symphony No. 8