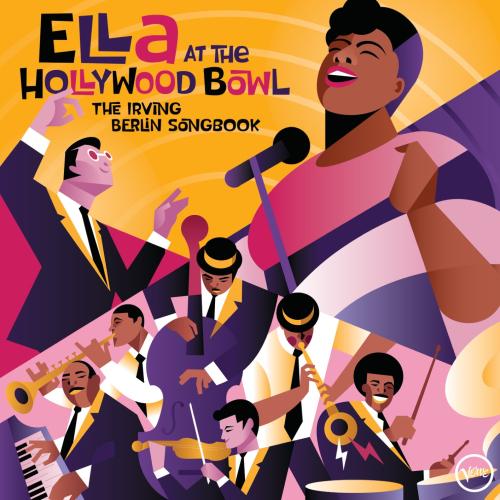

Ella At The Hollywood Bowl: The Irving Berlin Songbook Live (Remastered) Ella Fitzgerald

Album info

Album-Release:

2022

HRA-Release:

24.06.2022

Album including Album cover

I`m sorry!

Dear HIGHRESAUDIO Visitor,

due to territorial constraints and also different releases dates in each country you currently can`t purchase this album. We are updating our release dates twice a week. So, please feel free to check from time-to-time, if the album is available for your country.

We suggest, that you bookmark the album and use our Short List function.

Thank you for your understanding and patience.

Yours sincerely, HIGHRESAUDIO

- 1 The Song Is Ended (Live) 02:14

- 2 You’re Laughing At Me (Live) 03:26

- 3 How Deep Is The Ocean (Live) 03:07

- 4 Heat Wave (Live) 02:01

- 5 Suppertime (Live) 03:13

- 6 Cheek To Cheek (Live) 03:26

- 7 Russian Lullaby (Live) 01:51

- 8 Top Hat, White Tie and Tails (Live) 02:47

- 9 I’ve Got My Love To Keep Me Warm (Live) 03:06

- 10 Get Thee Behind Me Satan (Live) 04:00

- 11 Let’s Face The Music And Dance (Live) 02:50

- 12 Always (Live) 03:15

- 13 Puttin’ On The Ritz (Live) 02:01

- 14 Let Yourself Go (Live) 02:21

- 15 Alexander’s Ragtime Band (Live) 03:04

Info for Ella At The Hollywood Bowl: The Irving Berlin Songbook Live (Remastered)

"Ella At The Hollywood Bowl: The Irving Berlin Songbook," captures Ella Fitzgerald performing selections from her classic Irving Berlin Songbook at the legendary Hollywood Bowl with a full orchestra conducted and arranged by Paul Weston. This landmark record, discovered in the private collection of producer and Verve Records founder Norman Granz, marks the first time a live Songbook has been released from Fitzgerald.

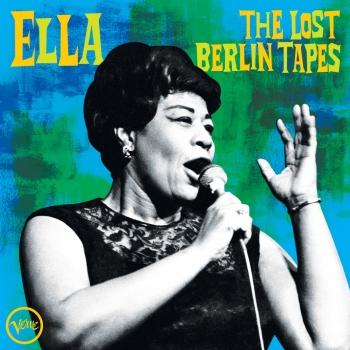

It is always amazing what audio treasures are discovered by professional diggers in company and private archives only many decades after they were recorded. Especially in the recent past, previously unknown masterpieces by John Coltrane ("Both Directions At Once: The Lost Album", "Blue World" and "A Love Supreme: Live In Seattle"), Thelonious Monk ("Palo Alto"), Charlie Parker ("Bird In LA") and Ella Fitzgerald ("The Lost Berlin Tapes") have seen the light of day.

Now, with "Ella At The Hollywood Bowl: The Irving Berlin Songbook", there is another sensational find of the "First Lady Of Song" from the private archive of her mentor and producer Norman Granz.

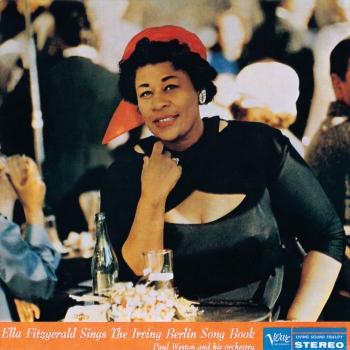

The album contains an absolutely fantastic live recording made on 16 August 1958 at the Hollywood Bowl; only five months after the singer had recorded the double album "Ella Fitzgerald Sings The Irving Berlin Song Book" for Verve Records. This fourth album in the groundbreaking and incredibly popular "Songbook" series earned Ella two trophies at the first-ever Grammy Awards on 4 May 1959: for "Best Jazz Performance by a Single Artist" and "Best Female Vocal Performance" in the pop category. In addition, the "Irving Berlin Songbook" was also nominated for the "Album of the Year" award.

With an orchestra conducted and arranged by Paul Weston, Ella presented 15 of the 31 songs from the then brand-new double album in the completely sold-out Hollywood Bowl. It was to remain the only concert in which she performed the iconic arrangements live with a full orchestra, as in the studio session also conducted by Weston. The programme featured some of Irving Berlin's best-known songs, including timeless ballads like "How Deep Is The Ocean?" and "Supper Time", the Hollywood movie songs "You're Laughing At Me" and "Get Thee Behind Me Satan", as well as the swinging up-tempo numbers "Cheek To Cheek", "Top Hat", "I've Got My Love To Keep Me Warm", "Heat Wave" and "Puttin' On The Ritz'". The completely enthusiastic audience inspired Ella on this evening to performances that were even more electrifying than those of the previously made studio recordings.

Gregg Field used the original quarter-inch tapes to mix the immaculate and sonically lush live tracks. Field, who has already won eight Grammys for his work as a producer and sound engineer, had accompanied Ella on tour himself in the mid-80s as a drummer. The album is rounded off by a knowledgeable accompanying text by the well-known jazz author and music critic Will Friedwald about the concert and the entire Songbook series. The legendary Songbook albums, on which Ella interpreted the best songs of the greatest US composers in an incomparable way, were the cornerstone of the Verve catalogue and set a new standard for jazz vocal recordings that has still not been surpassed since.

Ella Fitzgerald, vocals

The Hollywood Bowl Pops Orchestra

Paul Weston, conductor

Digitally remastered

Liner notes by Will Friedwald: “The song is ended, but the melody lingers on.” The Roaring ’20s may have been “The Jazz Age,” but Irving Berlin, basking in the warm romantic glow of his recent (1926) marriage, composed some of his most heartfelt ballads – and waltzes no less – in this period, among them, “Always,” “Remember,” “All Alone,” “What’ll I Do?” and “Russian Lullaby.” Although it’s a song which, like many others, laments over a lost love, “The Song Is Ended” better describes a beginning, rather than an ending, in the actual chronology of the songwriter’s life. That’s why, quixotic as it might sound, it was appropriate for Ella Fitzgerald to open her set of Irving Berlin songs at the Hollywood Bowl on Saturday, August 16, 1958 with “The Song Is Ended.”

Thus, Fitzgerald chose to open this show with a song that most people would have thought of as a closer, and that’s not even one of the most remarkable aspects of this performance. More importantly, although she performed on numerous occasions in the Bowl, this is the first full-length set by Fitzgerald from this iconic venue to be released. For another, it’s the only time she worked in “public appearance” with Paul Weston, the gifted arranger-conductor of her Irving Berlin Songbook album. Most importantly this is an exceedingly rare occasion where Fitzgerald (or any of her contemporaries) took the repertoire from one of her studio albums and performed it live in concert – and at the Bowl no less – with the actual arranger who had done the album.

Actually, it was two albums that she performed live at the Bowl on this evening: the first half was titled “Ella Fitzgerald Sings Cole Porter,” which was followed by “Ella Fitzgerald Sings Irving Berlin.” (A year later, she would sing an entire evening of George and Ira Gershwin songs with Nelson Riddle, in anticipation of the next entry in the songbook series.) Exactly how and why Fitzgerald and her manager-producer Norman Granz decided to mount such a concert isn’t known. Fitzgerald’s live appearances followed several formats, and this wasn’t one of them. In her early big band years, roughly 1935 to 1942, she sang primarily in ballrooms, with the Chick Webb Orchestra (and subsequently with the same group under her own nominal leadership) for a mostly dancing audience, and also, occasionally, at movie theaters like the Apollo. During and after the war, she worked in supper clubs both of the mainstream and jazz variety as well as theaters. But even as her popularity and prestige increased to the point where she could work in formal concert halls, she mostly maintained the nightclub format – i.e. a mixed collection of songs without a specific theme (and certainly never deriving from a single album), usually accompanied by a trio. (When she toured with Jazz at the Philharmonic, the main difference was that, in addition to her own set, she would also do a few additional numbers with some of the headliners of the troupe in what the impresario described as a “jam session.”)

But to come on stage – with a full orchestra – and essentially sing the contents of a studio album, well, nobody did that. Not Sinatra, not Tony Bennett, not Miles Davis, nor any of the other key innovators who contributed to the development of what came to be known as “the concept album.” Even Duke Ellington only rarely performed a full-length work, such as one of his many “suites,” all the way through. (It wasn’t until years later that rock bands like the Who would make a point to tour playing the entirety of an album like Tommy – admittedly an extreme example.)

So exactly why did Fitzgerald and Granz choose to face this particular music and dance in this singular fashion? We may never know, but the logical answer is that the songbooks were proving to be such a major component to her burgeoning career that, for at least two years in a row, Fitzgerald and Granz were determined to do something special in honor of the ongoing series.

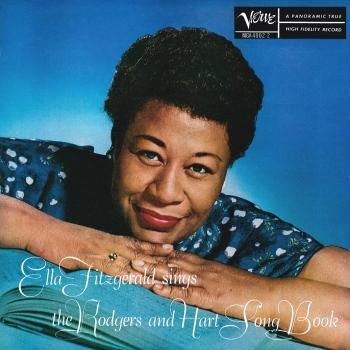

Ella’s first songbook album had been her original 10” Ella Sings Gershwin, produced by Milt Gabler, in 1950. When Granz was able to secure her exclusive recording contact in 1955, he immediately proceeded to build an entire new label – Verve Records – around her, with the songbook series as a foundational component of the Verve catalog. Indeed, all five of her first albums for the label (released in ’56 and ’57) were either songbooks or duet sessions with her longtime inspiration, Louis Armstrong. The songbook series was a major success commercially right from the git-go, but actually started somewhat tepidly in an artistic sense, in that the first two (Cole Porter and Rodgers and Hart) had arrangements by a decidedly lesser musical director. However, the series perked up considerably with the third, Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Duke Ellington Songbook, an ambitious four-LP package co-starring the Maestro and his orchestra.

The fourth, Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Irving Berlin Songbook, had been partly instigated by the songwriter himself, who was so impressed with the first three Songbook albums released thus far that he offered to cut his standard royalty rate in half. For the Berlin project, Granz recruited one of the best arranger-conductors then working in popular music, the formidable Paul Weston (1912–1996) and the results were impressive. Weston had first won his wings as a staff writer for Tommy Dorsey and then the Bob Crosby Orchestra, and then enjoyed long-term professional relationships with singers Dinah Shore and Jo Stafford, the latter becoming Mrs. Weston in 1952. His was the usual trajectory of an arranger-conductor in that period: big bands to popular singers and eventually to television (mostly variety shows), but his work was anything but average. Rather, Weston was a musical director in the same skill level as Sinatra’s two greatest collaborators, Axel Stordahl and Nelson Riddle.

As mentioned, Fitzgerald’s concert of August 16, 1958, was divided into two acts, “Ella Fitzgerald sings Cole Porter” and “Ella Fitzgerald Sings Irving Berlin.” Both halves opened with instrumental music – as a kind of an overture – conducted by Weston. Act One commenced with a “Cole Porter Overture” by Robert Russell Bennett, at that time long Broadway’s most celebrated orchestrator, along with Weston arrangements of two Porter songs. Act Two began with Weston playing Berlin’s “Blue Skies” as well as excerpts from his own extended work, Crescent City Suite, recently released by Columbia Records.

The officially-released recording of these arrangements, the Berlin Songbook, as issued by Verve in 1958, was one of Fitzgerald’s strongest albums thus far, but as outstanding as her studio work always was, her live concerts were just better: livelier, more energetic and more ebullient. Like all of her colleagues and peers (especially Sinatra and Nat Cole), Fitzgerald always fed off the energy and enthusiasm of the crowds in front of her. (It’s hardly a surprise that the best-remembered album of her entire career was probably her iconic 1960 Berlin concert recording.)

Thus, the ballads, among them such classics as “How Deep Is the Ocean?” and “Supper Time,” as well as such lesser-known Berlin Hollywood tunes as “You’re Laughing at Me” and “Get Thee Behind Me Satan,” are more openly emotional and moving. Two mid-’20s waltzes, “Always” and “Russian Lullaby” (a 16-bar minor key masterpiece) are amazingly effective. One wishes she had kept the latter in her repertoire; a rare example of Fitzgerald using wordless singing to comfort an infant rather than ignite a roaring crowd, it might have been another “Summertime” for her.

But though she was a supreme balladeer, The First Lady of Song was always more celebrated for her swinging uptempo numbers, as represented here by “Cheek to Cheek,” “Top Hat,” “I’ve Got My Love to Keep Me Warm” (“warm, warm, warm!”), the exotic “Heat Wave” (which is also warm, warm, warm!), “Puttin’ on the Ritz” (“well, I changed that melody!” she says afterwards), and “Let Yourself Go” (“Wail!” she exhorts to a muted trumpet soloist). “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” is a uniquely conceptual arrangement by Weston, which contrasts the agitated 2/4 of 1911-style dixieland with smoother, contemporary style “cool” jazz – it’s very specific to its era without being dated.

As mentioned, the Berlin half of the concert began with Paul Weston playing his own instrumental arrangement of “Blue Skies” – which opens the door to a mini-mystery involving that archetypical Berlin song. Fitzgerald and Weston recorded it, along with 31 other Berlin songs, at the fourth of five sessions devoted to the album in March 1958. Yet for whatever reason, “Blue Skies” wasn’t included in the original US issue of the album (either on the mono or stereo editions) though it was restored years later. (That same track of “Blue Skies,” however, was included as part of Fitzgerald’s Get Happy album in 1959.)

Of the 32 Berlin songs recorded for the project (15 of which were performed at this Bowl concert), “Blue Skies” was the album’s major scat feature – and one of Fitzgerald’s all-time greatest. (Making it all the more curious that it wasn’t used on the original album.) But since “Blue Skies” was absent from both the original double album and the Bowl concert, the decision was made to increase the scattiness quotient of “The Song Is Ended.” Even more than on the album, the live treatment of “The Song is Ended” repurposes Berlin’s melancholy waltz into an exuberant 4/4 swinger, complete with brief wordless episodes.

The transformation is so complete that it makes perfect sense that she would use it for an opener rather than a closer – underscored by the way she repeats “the melody lingers on…and on…and on.…” Even though it’s usually performed as a sad song, Fitzgerald shows how it works just as well as a joyous ode to the very act of making music; how better to take our happiness while we may? The title may tell us that the tune has concluded, but the woman whom Mel Torme christened “The High Priestess of Song,” is showing us precisely the opposite. (In fact, the tapes of the 1958 Cole Porter material, as well as the entire 1959 Gershwin-Nelson Riddle concert, will hopefully be issued sooner rather than later.) The song, and the adventure of making music with Ella Fitzgerald, are just beginning.

Ella Fitzgerald (1917-1996)

was, along with Sarah Vaughan and Billie Holiday, one of the most important vocalists to emerge from the big-band era. Her style is marked by a sunny outlook, a girlish innocence, and a virtuoso command of her voice.

Fitzgerald was born out of wedlock in Newport News, Virginia, to a laundress mother and a father who disappeared when she was three years old. Along with her mother and her mother’s new boyfriend who functioned as a stepfather, she soon moved to Yonkers, New York, where she began her schooling. Around the third grade she started dancing, a pursuit that became almost an obsession. In 1932, when she was fifteen, her mother died suddenly of a heart attack. Her stepfather treated her badly, but an aunt took the teenager to live with her in Harlem. This arrangement did not last long; Fitzgerald ran away in 1934 to live on the streets.

Late that year she won a talent contest at the Apollo Theater; she had entered as a dancer, but nervousness caused her to sing instead. Several months later she joined drummer Chick Webb’s big band, where she mostly sang novelties like 'Vote for Mr. Rhythm'. In 1938 she recorded 'A-Tisket, A-Tasket', her own adaptation of a turn-of-the-century nursery rhyme, which took the country by storm and eventually sold a million copies. When Webb died in 1939 the band’s management installed Fitzgerald as leader.

In 1942 the band broke up and Fitzgerald became a single act, touring with various other popular names of the day. She also became interested in scat singing and the newly emerging style known as bebop, and in 1945 she recorded a landmark version of 'Flying Home.' Several tours with the Dizzy Gillespie band also contributed to her assimilation of the bebop style.

In the late 1940s Fitzgerald began to tour with the Jazz at the Philharmonic troupe, working with such leading musicians as saxophonist Lester Young, trumpeter Roy Eldridge, pianist Oscar Peterson, and bassist Ray Brown, to whom she was married for four years. JATP impresario Norman Granz became increasingly influential in her career, and in 1953 he became her manager.

Three years after that he became her record producer as well, recording her on his own Verve label. He wasted little time in having Fitzgerald record a double album of Cole Porter songs. Fitzgerald made many wonderful albums for Verve in the following decade, but the six songbooks occupy a special place in her discography. They were instrumental in expanding Fitzgerald’s appeal beyond that of a 'jazz singer' and creating a demand for her in venues not usually open to jazz artists.

For die-hard jazz fans, though, the well-polished jewels of the songbook series lack the raw energy of Fitzgerald’s live performances. Happily, Granz released several landmark concert albums by her as well. Especially exciting was a 1960 Berlin concert, which featured an electrifying performance of an impromptu take on 'Mack the Knife,' which became a Top 30 single. Fitzgerald usually performed with a trio or quartet, but there were also appearances with larger groups, such as the Duke Ellington and Count Basie orchestras.

By the 1960s Fitzgerald had become wealthy enough to retire, but the love of performing drove her on — she appeared regularly until just a couple of years before her death in 1996. Sidemen came and went, but except when health problems intervened she performed as much as humanly possible, sometimes singing concerts in two different cities in one day. Source: Verve Music (Phil Bailey). Excerpted from Ken Burns’ Jazz: The Definitive Ella Fitzgerald

This album contains no booklet.