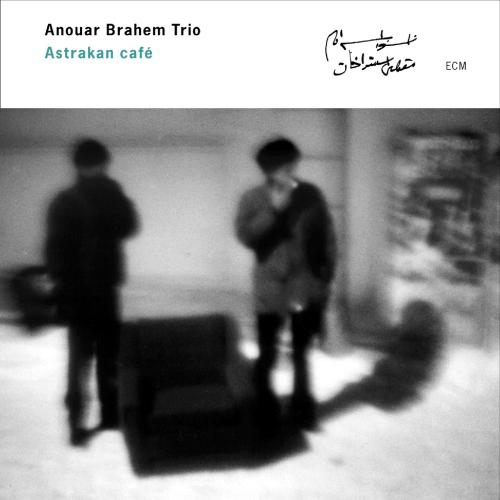

Astrakan Café Anouar Brahem Trio

Album info

Album-Release:

2000

HRA-Release:

12.08.2013

Album including Album cover Booklet (PDF)

I`m sorry!

Dear HIGHRESAUDIO Visitor,

due to territorial constraints and also different releases dates in each country you currently can`t purchase this album. We are updating our release dates twice a week. So, please feel free to check from time-to-time, if the album is available for your country.

We suggest, that you bookmark the album and use our Short List function.

Thank you for your understanding and patience.

Yours sincerely, HIGHRESAUDIO

- 1 Aube rouge à Grozny 04:23

- 2 Astrakan Café (1) 03:19

- 3 The Mozdok's Train 04:47

- 4 Blue Jewels 07:24

- 5 Nihawend Lunga 03:32

- 6 Ashkabad 05:38

- 7 Halfaouine 05:58

- 8 Parfum de Gitane 07:05

- 9 Khotan 03:31

- 10 Karakoum 05:08

- 11 Astara 10:47

- 12 Dar es Salaam 03:48

- 13 Hijaz pechref 06:24

- 14 Astrakan Café (2) 04:49

Info for Astrakan Café

Tunisian oud master Anouar Brahem has singlehandedly rewritten the history of his instrument, elevating its status to self-contained orchestra. Like a film director whose camera is a third eye, he paints in moving images—no coincidence, given that much of his music is written for screen and stage. His virtuosity is the pulsing stuff of life and therein lies the power of his music, itself a language beyond the grasp of this meager orthography. Astrakan Café is among his best records, for the solemnity of its nourishment is as attuned to the ether as the two musicians who aid in Brahem’s quest to describe its taste. Turkish clarinetist Barbaros Erköse returns after his invaluable contributions to Conte de l’incroyable amour, intense as ever in the spine-tingling depth of his song. Percussionist and longtime Brahem collaborator Lassad Hosni brings likeminded expertise to the table, adding just the right dash of spice to every tune.

Of those tunes we receive a lavish tale, each chapter a depth-sounding such as only Brahem can elucidate. As a meeting place, the titular café lends itself to intimate conversations and a feeling of community across borders. It introduces us to the protagonists of an epic, cohesive narrative. Erköse’s opening gambit in “Aube rouge à Grozny” cuts straight to the marrow, his notes captured at the height of their emotional density. If this is the defining of a door, the title track is the opening of it. Brahem’s plectrum takes its first dance steps into the morning, the streets fresh with vendor smoke and tourist chatter. Beyond them is “The Mozdok’s Train,” in which the trio comes together in the spirit of travel, not as outsiders but as those whose home is wherever they happen to be: disciples to no one but the steps they have yet to take. Brahem chooses his words carefully. He rallies heroes and villains, spirits and the lowly, in a single breath and submits them to his verbal employ. Little do the passengers know that in the next car over, wedged between a folded shirt and a thumb-printed map, is a box of “Blue Jewels.” Brahem sets the stage as Erköse inlays the clasp that keeps those secrets locked. Hosni jacks up the train’s speed. His are the fingers drumming on the stretched leather of a many-stickered suitcase, the conductor’s practiced hand on burnished controls. A memory assails this assailant, a vision of love long buried until now. It awakens in him the will to change in “Nihawend Lunga,” which moves at a clip so untouchable that its eyes bleed silk, a spider’s web for the prey of “Ashkabad.” Erköse flings cries backward and sideways, writhing in the vision of a life he could have had. And just before the train drowns in the darkness of a tunnel, he jumps from an open door and into the mirage of “Halfaouine.” He awakens to the themes of a passing caravan and clutches his prize even as the “Parfum de Gitane” seeks him out like a desert oasis. He listens to the elder sharing tales in “Khotan,” a solo track from Brahem. Youth returns in “Karakoum” as if time has reversed. This lifts his spirit to the realm of “Astara.” Here feet tread lightly but surely, using mountains as stepping-stones to walk across distant suns. Erköse’s haunting monologue, rendered in hourglass shape, inspires a measured line of flight through the alleys of “Dar es Salaam,” across the waters of “Hija pechref,” and back to the album’s title scene, sipping at the bitter fruits of the earth until these fantasies become apparent to us, ephemeral like the swirl of cream that pales into sepia drink.

Anouar Brahem’s oud playing is expressive, entrancing and beautiful. It’s so moving and anthemic it’s hard to believe any listener wouldn’t be frequently overwhelmed by Brahem’s brilliance. While one can debate whether Brahem’s music should be considered jazz or world or some hybrid of the two, there’s no denying the songs on Astrakan Café rank among the most lyrical and elegant in any genre. Brahem blends elements of traditional Arab and Islamic religious and popular music with just a slight nod to the American improvising tradition. ... Barbaros Erköse, on clarinet, and Lassad Hosni, on percussive instruments bendir and darbouka, prove equally exciting players. (Ron Wynn, Jazztimes)

Anouar Brahem, oud

Barbaros Erköse, clarinet

Lassad Hosni, bendir, darbouka

Anouar Brahem

was born in 20 th October 1957 in Halfaouine in the Medina of Tunis. Encouraged by his father, an engraver and printer, but also a music lover, Brahem began his studies of the oud, the lute of Arab world, at the age of 10 at the Tunis National Conservatory of Music, where his principal teacher was the oud master Ali Sriti. An exeptional student, by the age of 15 Brahem was playing regularly with local orchestras. At 18 he decided to devote himself entirely to music. For four consecutive years Ali Sriti received him at home every day and continued to transmit to him the modes, subtleties and secrets of Arab classical music through the traditional master / disciple relationship.

Little by little Brahem began to broaden his field of listening to include other musical expressions, from around the Mediterranean and from Iran and India... then jazz began to command his attention. "I enjoyed the change of environment," he says" and discovered the close links that exist between all these musics".

Brahem increasingly distanced himself from an environment largely dominated by entertainment music. He wanted more than to perform at weddings or to join one of the many existing ensembles which he considered anachronistic and where the oud was usually no more than an accompanying instrument for singers. A deepfelt conviction led him to give first place to this preferred instrument of Arab music and to offer the Tunisian public instrumental and oud solo concerts. He began writing his own compositions and gave a series of solo concerts in various cultural venues. He also issued a self-produced cassette, on which he was accompanied by percussionist Lassaad Hosni.

A loyal public of connoisseurs gradually rallied around him and the Tunisian press gave enthusiastic support. Reviewing one of Brahem's first performances, critic Hatem Touil wrote: "this talented young player has succeed not only in overwhelming the audience but also in giving non -vocal music in Tunisia its claim to nobolity while at the same time restoring the fortunes of the lute. Indeed, has a lutist produced such pure sounds or concretised with such power and conviction, the universality of musical experience"

In 1981, the urge to seek new experiences became ever stronger and his departure for Paris, that most cosmopolitan of cities, enabled him to meet musicians from very different genres. He remained for four years, composing extensively, notably for Tunisian cinema and theatre. He collaborated with Maurice Béjart for his ballet "Thalassa Mare Nostrum" and with Gabriel Yared as lutist for Costa Gavras’ film "Hanna K.".

In 1985 he returned to Tunis and an invitation to perform at the Carthage festival provided him with the opportunity of bringing together, for "Liqua 85" , outstanding figures of Tunisian and Turkish music and French jazz. These included Abdelwaheb Berbech, the Erköse brothers, François Jeanneau, Jean-Paul Celea, François Couturier and others. The success of the project earned Brahem Tunisia's Grand National Prize for Music.

In 1987, he was appointed director of the Musical Ensemble of the City of Tunis (EMVT). Instead of keeping the large existing orchestra, he broke it up into formations of a variable size, giving it new orientations: one year in the direction of new creations and the next more towards traditional music. The main productions were "Leïlatou Tayer" (1988) and "El Hizam El Dhahbi" (1989) in line with his early instrumental works and following the main axis of his research. In these compositions, he remained essentially within the traditional modal space, although he transformed its references and upset its heirarchy. Following a natural disposition towards osmosis, which has absorbed the Mediterranean, African and Far-Eastern heritages, he also touched from time to time upon other musical expressions: European music, jazz and other forms.

With "Rabeb" (1989) and "Andalousiat" (1990), Anouar Brahem returned to classical Arab music. Despite the rich heritage transmitted by Ali Sriti and the fact that this music constitued the core of his training, he had in fact, never performed it in public. With this "return" he wished to contribute to the urgent rehabilitation of this music. He put together a small ensemble, a "takht", the original form of the traditional orchestra, where each instrumentalist plays as both a soloist and as an improviser. Brahem believes this is the only means of restoring the spirit, the subtlety of the variations and the intimacy of this chamber music. He called upon the best Tunisian musicians, such as Béchir Selmi and Taoufik Zghonda, and undertook thorough research work on ancient manuiscripts with strict care paid to transparency, nuances and details. For more information visit: http://www.anouarbrahem.com

Booklet for Astrakan Café