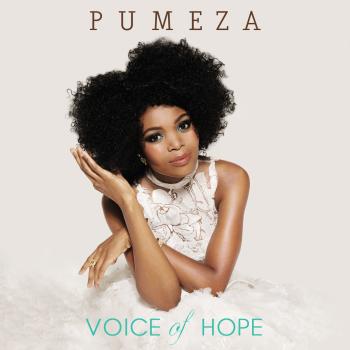

Pumeza Matshikiza

Biography Pumeza Matshikiza

Pumeza Matshikiza

It’s 6,000 miles from Cape Town to London, but the distance which Pumeza Matshikiza has travelled can’t be measured in mere geography. To be brought up in the townships of South Africa and then to make the giant leap into a professional operatic career and a major label recording contract, despite having had a minimum of formal music training while she was growing up, is an awesome feat indeed.

“We never studied musical notation or any history of music,” Pumeza recalls. “It was just tonic sol-fa. But I sang in choirs and I grew up with choral and church music. We sang pieces by our own composers, then as I grew older we were introduced to oratorio choruses, with pieces from Haydn’s The Creation for example. Later on, going in the direction of opera was a continuation of this kind of background. ”

Her first exposure to opera was by hearing it on the radio, and she’d also visit the public library with a school friend and borrow opera LPs to listen to. One of the first names she became aware of was the Swiss soprano Edith Mathis, who she heard singing Susanna in Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro.

Today, as she prepares her first solo album for Decca, Pumeza is a regular performer with Stuttgart Opera, and can look back on the variety of professional roles she has sung after graduating from London’s Royal College of Music, but her past remains vivid to her. She remembers living in her father’s family house in the Eastern Cape, then after her parents split up she moved with her mother to the Cape Town area.

“I think of myself as someone who comes from Cape Town, because that’s what I know. I remember as a young person living in different townships, because my mother wanted to have a house and we changed places frequently. I went to about four primary schools and then stayed in high school for five years.”

Pumeza was growing up as her homeland emerged from apartheid at the beginning of the 1990s. She couldn’t avoid being affected by the bitter conflicts the regime provoked.

“I remember people marching and singing songs about freedom, and the police coming with tear gas on certain days. There would be big yellow police cars which came to bring order, and I also remember some days coming from school and there would be people burning others. They called it necklacing – they put a tyre round their necks and poured on petrol, because they said these people were spies. It was shocking. As children we were not supposed to see these things, but that was the time we lived in.”

Her mother was also a keen amateur singer who performed with Seventh Day Adventist church choirs, but wasn’t able to give her daughter private musical tuition. “I wish I could have played piano,” says Pumeza. “It would have been a great essential skill to have, but if you have a single parent who’s worrying about what you’re going to eat, it’s difficult to think about piano lessons.”

Still, she was at least blessed with artistic genes. She’s a member of the extended Matshikiza family, which has its roots in the Eastern Cape and has also produced the jazz musician and composer Todd Matshikiza and his son John, an actor, theatre director and journalist. Todd wrote the jazz opera King Kong (about the dramatic life of South African boxer Ezekiel Dlamini) which became a hit in South Africa at the end of the 1950s and then transferred successfully to London. Serendipitously, it was released by Decca. Todd died in 1968 before Pumeza was born, and John in 2008.

“I never got to meet John, but I met his mother Esme,” she says. “We started talking and we realised that I must have been related to Todd. In South Africa, you have a surname and also a clan name. If you have the same surname and clan name, that means you come from the same line.”

Yet for a time, it looked as if Pumeza’s future wouldn’t be based around music at all. Opera, considered a highfalutin’ pursuit of the European elite, didn’t register at all on the cultural radar in the townships. Since she displayed an aptitude for maths and science at school, “one of my teachers registered me to study to be a quantity surveyor at the University of Cape Town. I was totally bored, and sometimes I didn’t even attend classes. I was based on the upper campus of the university, and the lower campus is where the South African College of Music is. I’d go down there and hear people playing piano and singing, and I’d think ‘oh, I so want to be there!’ So eventually I went and registered myself at the college of music.”

Since Pumeza lacked the nuts and bolts of musical theory, she had to do a crash course in the basics.

“If somebody put some music in front of me I wouldn’t know where C or G or A was,” she admits. “I didn’t know scales and I hadn’t learned the piano. I had lessons at college, and I was 21 and I was thinking ‘what I’m learning now is something a six-year-old should be doing!’ I was playing scales in the left hand, right hand and then both hands and playing little songs. I think the tutors knew there was only so much we could do because you need to start very young, but at least I learned where the notes are. The more music you do, the more you can follow the melody and read the notes on the page.”

It was while she was at music college that she was spotted by South African composer Kevin Volans. He caught his first glimpse of Pumeza when she visited London with a group of South African singers, and was singing the role of Frasquita in Bizet’s Carmen in a performance at Wilton’s Music Hall in Aldgate. He asked her if she’d audition for a new opera he was writing for the Handspring Puppet Company (who would later create War Horse for the National Theatre).

“I said yes, why not,” Pumeza recalls. “The piece was The Confessions of Zeno, I sang Purcell’s Dido’s Lament for my audition, and I got the part. I took a year off from college to be part of the project, and we travelled all around Europe – Rome, Paris, Zagreb, Salamanca, Kassel in Germany.”

Afterwards, Volans asked Pumeza what she planned to do when she finished her course in Cape Town.

“I said I’d like to go overseas to further my studies, because opera is really a European art form and I think I’d learn a lot by going to Europe. Also I wanted to work on my European languages, and just get experience and develop further. So Kevin arranged for me to audition at the Royal College of Music in London, and he said he’d pay for my ticket and I shouldn’t worry about it if they don’t take me – I should just treat it like a holiday in London. I thought that’s great, because I won’t be under any pressure.”

Pumeza had also planned to audition for some other colleges while she was in the UK, but the RCM told her not to bother since they were going to offer her a full scholarship. That took care of her tuition fees, while opera-loving philanthropist Peter Moores agreed to cover her living expenses after he’d heard her sing. It was the start of Pumeza’s great adventure.

“Professor Virginia Davids, my college singing teacher, always said she thought I was going to travel a lot in the future and I’d have to learn to be my own friend, because it’s not easy to stay away from home. I guess she was right. In the beginning London was a shock – how busy everyone was, and everything happening at double the speed I was used to in South Africa. In fact the weather was the thing that really shocked me the most. I did sometimes ask myself ‘why am I here, why am I doing this to myself?’ At times I cried I think.”

Fortunately she stuck with it, and soon began to shine in student opera productions. Described by the RCM’s Head of Vocal Studies Neil Mackie as “probably the most promising soprano to come our way in the last 10 years,” she graduated with an Advanced Diploma in Performance in 2007, then was accepted into the Jette Parker Young Artist scheme at the Royal Opera House. This afforded her some priceless performing opportunities, including a chance to sing the role of the Queen’s page in Verdi’s Don Carlo at Covent Garden, and meant that she participated in masterclasses with such opera greats as Kiri Te Kanawa, Renata Scotto and Ileana Cotrubas.

Subseqent landmarks have included her acclaimed performance in the title role of Mozart’s Zaide with the Classical Opera Company at Sadler’s Wells, and her first prize in the Veronica Dunne Singing Competition in Dublin in 2010. “I personally don’t like competitions, because I don’t think music or singing is something to compete about,” she admits. “But yes, I won that competition, and it was great that I won!”

Her three-year contract with Stuttgart Opera has been an eye-opening introduction to the challenges and pressures of an operatic career, and has pushed her through roles in everything from Wagner’s Parsifal to Weber’s Der Freischutz and Denisov’s L’Ecume des Jours. Meanwhile, she has been absorbed in helping to plan and refine the material for her Decca debut. The album will depict her musical journey from the South African townships to the operatic stage through a mix of operatic arias, traditional African songs in her native Xhosa language, compositions by Kevin Volans and Todd Matshikiza, and pieces in which she’s accompanied by an African choir, including a new arrangement of Paul Simon’s Homeless, from his Graceland album.

“It’s a long process to arrange the different pieces and find what works best,” she says. “When I do concerts I do classical pieces and then some South African songs at the end. The South African music is natural to me, but it will sound a little different from somebody who hasn’t been trained classically. You sing with a different emotion. It’s about feel, and you have to trust the music.”