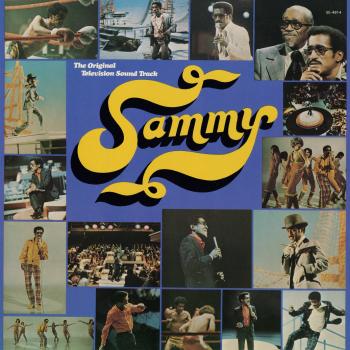

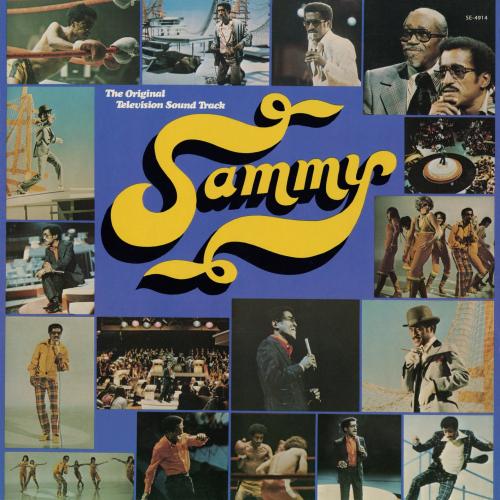

Sammy: The Original Television Soundtrack (Remastered) Sammy Davis Jr.

Album Info

Album Veröffentlichung:

1973

HRA-Veröffentlichung:

12.12.2025

Das Album enthält Albumcover

Entschuldigen Sie bitte!

Sehr geehrter HIGHRESAUDIO Besucher,

leider kann das Album zurzeit aufgrund von Länder- und Lizenzbeschränkungen nicht gekauft werden oder uns liegt der offizielle Veröffentlichungstermin für Ihr Land noch nicht vor. Wir aktualisieren unsere Veröffentlichungstermine ein- bis zweimal die Woche. Bitte schauen Sie ab und zu mal wieder rein.

Wir empfehlen Ihnen das Album auf Ihre Merkliste zu setzen.

Wir bedanken uns für Ihr Verständnis und Ihre Geduld.

Ihr, HIGHRESAUDIO

- 1 Introduction (Remastered) 00:06

- 2 (I'll Be Glad When You're Dead) You Rascal You (Remastered) 01:09

- 3 This Dream (Remastered) 02:14

- 4 Narration / Birth Of The Blues (Remastered) 03:07

- 5 Mr. Bojangles (Single Version) (Remastered) 05:43

- 6 Narration / I've Gotta Be Me (Remastered) 01:00

- 7 Get It On (Remastered) 04:11

- 8 Over the Rainbow (Remastered) 03:27

- 9 Porgy & Bess Medley (Remastered) 01:25

- 10 It Ain't Necessarily So (Remastered) 01:38

- 11 Bess, You Is My Woman Now (Remastered) 02:18

- 12 There's A Boat That's Leaving For New York (Remastered) 02:27

- 13 Narration (Remastered) 00:21

- 14 For Once In My Life (Album Version) (Remastered) 02:50

- 15 I'm Not Anyone (Single Version) (Remastered) 04:09

- 16 Narration (Part 2) (Remastered) 01:34

- 17 Birth Of The Blues (Remastered) 03:05

- 18 Ending / I've Gotta Be Me (Remastered) 00:23

Info zu Sammy: The Original Television Soundtrack (Remastered)

In April 1973, David W. Tebet, the Vice President for Talent for NBC announced a splashy long-term contract between the network and Sammy Davis, Jr. The deal gave NBC exclusive use of Sammy’s talents on television in the USA. “This is one of the most important individual talent agreements ever entered into by NBC and we are pleased to acquire Sammy’s exclusive television services,” said Tebet.

NBC’s first use of Sammy would be to launch a new variety series, NBC Follies that September, following a successful pilot in February. But they also had in mind a big one-hour TV special. Titled Sammy, it would be billed as celebrating Sammy’s 45th year in the business. Sammy’s label, MGM Records, would release the soundtrack on LP. Sammy got to work. A portion of the special would be filmed with a live audience in June, and a second portion filmed on sound stages in September. Both would be recorded in London.

The special was made in England because that was the base of operations the world’s best producer-director partnership in the field of televised musical specials – Gary Smith and Dwight Hemion. They had helmed specials for Barbra Streisand and Frank Sinatra, and been in charge of a Burt Bacharach special the previous year in which Sammy and Anthony Newley had performed an amazing 15-minute long medley of songs – Sammy knew he wanted the best in the business.

This, however, didn’t stop Sammy fighting their instincts. Sammy said “I fought Gary and Dwight all the way down the line because this was my life we were doing, I knew how we should do it – but they were right and I was wrong 1,000 per cent of the time!” The retrospective began with footage of a 7 year-old Sammy from Rufus Jones For President, singing “I’ll Be Glad You’re Dead, You Rascal You” and included a charming conversation with his father, Sammy Davis, Sr., reminiscing with Sammy about Sammy’s childhood and their early career together.

In the end, only two songs were utilised from the recordings made in front of a live audience at Grosvenor House in London: “For Once In My Life” and “The Birth of the Blues”. The remainder of the special was made up of set pieces filmed at ATV’s television studios: an outstanding rendition of “Mr. Bojangles”, a gaudy dance number, “Get It On”, which featured a bevy of bopping beauties and Sammy rocking some outrageous plaid pants, as well as a tasteful and touching take on “Over The Rainbow” and a medley of songs from Porgy And Bess.

The medley is the special’s high point. Despite being famous in the film for the role of Sportin’ Life, Sammy drops to his knees and begins the medley as Porgy, singing “I Got Plenty O’ Nuttin” and “Bess, You Is My Woman Now”. He sings “It Ain’t Necessarily So” as Sportin’ Life before a bit of split screen trickery sees Sammy join himself for a duet, cleverly combining “There’s A Boat Dat’s Leaving’ Soon For New York” with “Oh Lawd, I’m On My Way”. For 1973, it’s a triumph of timing, staging and technology. Sammy explained: “That was Dwight and Gary’s idea, and I fought them on it until they said, ‘Let’s try it once and see how it looks’ – and they were so right, and I was so wrong.”

One particularly noteworthy sequence involved a dramatic re-staging of the fight scene finale from Sammy’s 1966 Broadway production “Golden Boy”, in which Sammy’s character, boxer Joe Wellington, defeats the champ, José López. Dancer Jaime Rogers, who had played Loco on film in 1961’s West Side Story and had since become a successful choreographer, reprised his role as López, seven years after Sammy and he last did battle on a Broadway stage. Although Sammy was now more flyweight than welterweight, you can see how the fight must have captivated New York audiences, combining as it did elements of dance and music with a surprising degree of boxing authenticity.

The special ends with a song that was written specifically for Sammy by Paul Anka. Having written “My Way” for Frank Sinatra, Sammy had teased his friend about writing a song for him too. With Sammy being the ultimate spokesperson for the generic song of self-affirmation, it’s no surprise that “I’m Not Anyone” draws deeply from that well of inspiration. Curiously, Sammy recorded it during the Grosvenor House session, but with no audience in attendance – the eerie backdrop makes for an effective finish to the special.

Airing in the USA on 16th November, Sammy was hugely successful – especially by comparison to NBC Follies (its cancellation had already been announced). The Chicago Tribune called Sammy “one of the brightest, most exciting hours of performance that you’ll see on prime-time television this season”. Reviewer Cecil Smith wrote in The Los Angeles Times “It’s a retrospective of the career of this astonishing little man, and I doubt seriously that anything that occupies the tube this season will provide the breadth and depth of talent on display in this hour. It’s a virtuoso performance.”

MGM readied the soundtrack release for early December (and Christmas shopping). The closing songs were re-ordered so that the album would finish with “The Birth Of The Blues”, instead of “I’m Not Anyone”, but other than this all the songs and narration provided throughout the special were faithfully included. MGM also provided a special one-sided souvenir promo 45 of little 7 year-old Sammy’s performance of “I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead, You Rascal You” to the press.

Sammy Davis Jr.

Digitally remastered

Sammy Davis Jr.

lived from 1925 to 1990. Michael Heatley from Vox magazine gives a short biography.

In the over hyped world of popular music music, there are legends, and then there are Legends with a capital L. There’s no doubting which category Sammy Davis Jr falls into.

For a staggering 60 years, from his debut as a four year old child star in the late 1920’s to his untimely death in 1990 at the age of 64, he more than justified his title of ‘Mr Entertainment’ and when he wasn’t inspiring headlines on stage he was making news of it, as a founder member of the Rat Pack with fellow superstars Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin.

It’s impossible in the space allotted to do more than scratch the surface of one of showbiz’s all time greats. Thankfully, Sammy Davis Jr left no fewer than three detailed accounts of life at the top. ‘Yes I Can’ (1965) and ‘Life In A Suitcase’ (1980) were followed by ‘Why Me’, published the year before his death. All are required reading.

He owed his early start to his parents, vaudeville star Sammy Davis Sr and Puerto Rican ‘Baby Sanchez, who performed with the youngsters adopted uncle, Will Mastin, in his act ‘Holiday In Dixieland’. But Sammy Jr soon became the star of the show as the newly rechristened ‘Will Mastin’s Gang, Featuring Little Sammy’ acknowledged. When the authorities forbade him to appear, so legend has it his father shrugged his shoulders, gave his son a rubber cigar and billed him as a ‘dancing midget’.

Being a star has made it possible for me to get insulted in places where the average Negro could never hope to go and get insulted.

Whatever the truth, Sammy Davis jr’s career was off to a flying start. He made his film debut in the 1932 short Rufus Jones For President, showing off the tap dancing skills taught by the legendary Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson. War service first brought Davis face to face with racial prejudice (‘In show business we had our own protective system’, he later remarked), but he survived to resume his career with the Will Mastin Trio (completed by his father), and while touring with Mickey Rooney in the late forties played a three week Manhattan residency with bill topper Frank Sinatra. It was the beginning of a close and lifelong friendship.

During three decades, along all the highways of my youth, Frank had always been there for me.

A near fatal car crash in 1954 en route to Los Angeles recording session saw Davis lose his left eye, but a gruelling rehabilitation schedule left little time for self-pity; he was back on stage within weeks, wisecracking about his newly acquired eye patch. That spell in hospital coincided with a religions conversion to the Jewish faith which, while sincerely held for almost the rest of his life, provided the material for yet more self-mockery of the type that endeared him to an ever growing audience.

Although Davis made his debut in 1956s Mr Wonderful, Broadway would be an occasional, enjoyable distraction from the bulk of his career. He returned in 1964 as boxer Joe Wellington in a musical adaptation of Clifford Odet’s 1937 drama Golden Boy, both shows ran for over 400 performances.

Hollywood opened new doors for all-singing, all dancing Davis, his first notable role being Sportin” Life in a 1959 version of Gershwins Porgy And Bess. If anything, he suffered through his notoriety, despite his undoubted ability, people found it difficult to accept him in character roles like the embittered jazz musician in 1966’s A Man Called Adam. More successful perhaps were Rat Pack movies like Salt And Pepper (1968) and One More Time (1970) in which he simply played himself, while a brace of Cannonball Run films in the eighties afforded screen reunions with Dean Martin and others. Then in 1988, just two years before his death, he showed he could still dance by partnering Gregory Hines in the evocative Tap.

bio_photo2While Davis’s success broke down racial barriers, there were inevitably cries of “sellout” notably when he endorsed Republican President Richard Nixon in 1972. (Even James Brown confided ‘You’re taking a lot of heat…I never got it this way’). Yet every black performer all the way to nineties superstars Michael Jackson and Eddie Murphy (whose TV production company funded Davis’s last movie role in The Kid Who Loved Christmas) owe him a vote of thanks for his ground braking work both on and off camera.

‘Long before there was a civil rights movement’, he remarked in 1989, I was marching through the lobby of the Waldorf Astoria, of the Sands, the Fountainbleau, to a table at the Copa. I’d marched alone’. But it was his attitude to performance that broke barriers. Jolson had got the ball rolling, but too many taboos remained.’Dad said to me “You can’t do impersonations of a white person,” he once commented. ‘He really believed that’. Davis’s philosophy was a simple one. ‘Just do what you’re best at, he said in 1988, ‘and when you can’t do it any longer – stop’.

Sadly, the cancer that ended his life on 16th May 1990 made that decision for him, but he’d long since sung and danced his way into immortality. A final world tour in 1988/89 with Sinatra and Martin will long be remembered, even though Liza Minnelli had to take Dean’s place when ill health forced him to drop out. But Davis sang and danced on. ‘Sammy knew he was dying back then,’ Sinatra later revealed, ‘but you never expect it to come to that. We all think we’ll live forever.’

Sadly, of course, that doesn’t happen, but the magic of the music remains.

Three times married, Davis beat alcohol abuse, physical infirmity and the color bar and admitted he’d thrown away four fortunes gambling in Vegas and living the good life. Yet the musical legacy he left is priceless, and one that will surely endure for all time.

Dieses Album enthält kein Booklet