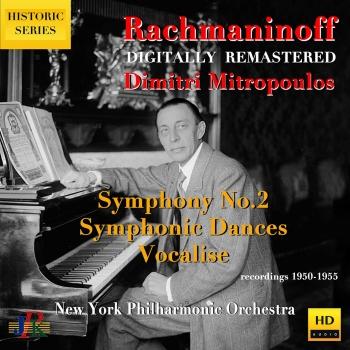

New York Philharmonic Orchestra & Dimitri Mitropoulos

Biographie New York Philharmonic Orchestra & Dimitri Mitropoulos

Dimitri Mitropoulos

showed musical talent from an early age: at ten years old, having started to learn to play the piano earlier, he was writing and playing his own compositions. His aptitude was noted by a member of the staff of the Athens Conservatory who encouraged him to pursue his musical studies. Having been born into a highly religious household, several of his relatives being priests of the Greek Orthodox church, Mitropoulos too considered becoming a priest, but the absence of music in the Greek Orthodox liturgy decided him in favour of music and he entered the Athens Conservatory, where he studied piano with Wassenhoven and harmony and counterpoint with Marsick. He graduated in piano in 1918 and in composition in 1920. While still a student he composed a symphonic poem entitled La mise au tombeau de Christ and his opera, Soeur Beatrice, based on a text by Maeterlinck, was performed at the Conservatory in 1920; Saint-Saëns was shown the score and later wrote favourably about it in a French journal. Mitropoulos was awarded a scholarship to study at the Brussels Conservatory with Paul Gilson during 1920 and 1921, after which he studied with Busoni in Berlin at the High School for Music until 1924. While in Berlin he also conducted as a substitute at the Berlin State Opera on Busoni’s recommendation.

Having returned to Greece, from 1924 onwards Mitropoulos conducted the Athens Conservatory Orchestra (which later became the Greek State Symphony Orchestra), exerting a major influence upon Greek musical taste by introducing into his programmes numerous previously unfamiliar and contemporary works. He was appointed professor of composition at the Conservatory in 1930, and in 1933 was elected a member of the Athens Academy. His international reputation was established in 1930 when, substituting for another Busoni pupil, Egon Petri, who was ill, he both conducted the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra and played the solo part in Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 3, a feat which he repeated in Paris and London during 1932. Mitropoulos toured Italy in 1933 and during the following year appeared in France, Italy, Belgium, Poland and Russia; he also appeared frequently in Monte Carlo and in 1935 was the guest conductor of the Lamoureux Orchestra in Paris.

In 1936, Mitropoulos was invited by Serge Koussevitzky to conduct the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and once again he enjoyed enormous success. The following year he appeared for the first time at the head of the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, again to great acclaim; and when the orchestra’s chief conductor, Eugene Ormandy, moved on to take over the Philadelphia Orchestra from Leopold Stokowski in 1938, Mitropoulos was appointed as the chief conductor. He moved to Minneapolis, where he lived simply. He became a popular local figure, and with no other permanent appointments to distract him, he entered whole-heartedly into encouraging amateur music-making in the community, in addition to his work with the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra where he programmed numerous contemporary works and gradually built up audiences to very high levels. As his biographer William R. Trotter noted, by 1940 ‘Minneapolis…officially had the largest per capita concert audience in America.’ In the same year the orchestra was contracted to the American Columbia label, and made the first commercial recording of Mahler’s Symphony No. 1, among many other works. Mitropoulos appeared in New York with the NBC Symphony Orchestra in 1939 and with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra for the first time during its 1940–1941 season. He took American citizenship in 1946, and for the 1949–1950 season shared the chief conductorship of the New York Philharmonic with Stokowski.

At the end of this season Mitropoulos was offered the post of chief conductor with the New York Philharmonic. As recordings of the broadcasts of many of his concerts with this ensemble clearly demonstrate, Mitropoulos was capable of driving the orchestra to unaccustomed heights; but at the same time he had a number of difficulties to contend with. Firstly his personality, which was essentially gentle and non-combative, was ill-suited to dealing with the toughness of the players in the orchestra, and with the manipulative working style of Arthur Judson, its manager: it is conceivable that Judson may have preferred the choice of Mitropoulos to that of Stokowski for this post, on the assumption that he would be a less strong character and therefore easier to manage, as may also have been the supposition with Sir John Barbirolli’s appointment to the orchestra before World War II. Secondly, Mitropoulos was frequently attacked by the New York critics, who disliked his programming, which at its best focused upon late-Romantic and modern European music rather than the staples of the traditional Austro-German repertoire and contemporary American music. Thirdly, his austere way of life and rumoured homosexuality fitted poorly with the McCarthyite mass psychology of the period. Not surprisingly in these circumstances, Mitropoulos’s days were soon numbered and his predicament was worsened by cardiac health problems which ultimately proved to be fatal. Following the unexpected death in 1956 of Guido Cantelli, who had been viewed as a potential successor, Leonard Bernstein openly campaigned for Mitropoulos’s position. As had been the case previously with Stokowski, Mitropoulos was invited to share the chief conductorship of the orchestra with Bernstein for the 1957–1958 season; but this was to be his last with the New York Phiharmonic and Bernstein took over as sole chief conductor with effect from the 1958–1959 season.

Despite these difficulties Mitropoulos was steadily building an enviable reputation as a conductor of opera, as well as of symphonic music, both in Europe and in America. He conducted productions of works such as Richard Strauss’s Elektra, Verdi’s Ernani, Mozart’s Don Giovanni, Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin and Puccini’s La fanciulla del West at La Scala Milan, the Maggio Musicale, Florence, the Salzburg Festival, the Chicago Lyric Opera and the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Once again recordings of these and many other works clearly demonstrate Mitropoulos’s great authority and skill as an operatic conductor. Valued by no less a judge of musical ability than Sir Rudolf Bing, he was invited to open the Metropolitan Opera’s 1958–1959 season with a new production of Puccini’s Tosca starring Renata Tebaldi and Mario del Monaco; while in Vienna, the musicians of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra were astounded that their colleagues in the New York Philharmonic had sought to remove him as their chief conductor. At the beginning of 1959, Mitropoulos suffered his first heart attack and was advised by his doctors to rest. However he was soon back on the podium, conducting both in America and in Europe; while rehearsing Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 with the Orchestra of La Scala, Milan, in November 1960, he experienced a further heart attack and died immediately.

Following his death Mitropoulos’s recordings rapidly vanished from sight. His reputation was not helped by the fact that his departure from the New York Philharmonic coincided with the end of the monophonic era in recording. Bernstein’s recordings appeared in the new medium of stereo, which eclipsed for a while all that had gone before, and attracted major press coverage, leaving older recordings very much on the sidelines. It was only with the gradual re-publication of broadcast recordings of opera and concert performances, especially in Italy and Greece, that Mitropoulos’s true stature as a musician began to be fully assessed and appreciated. His commercial discography is naturally centred upon his work in Minneapolis and New York. Although the overall quality of Mitropoulos’s studio recordings is extremely high, nevertheless to gain an even fuller understanding of this prodigious musician it is necessary to turn to the recordings of his live performances. In these above all else, Mitropoulos’s highly personal musical character is fully apparent throughout, and his extraordinary ability to animate to the highest degree all the music which he conducted.