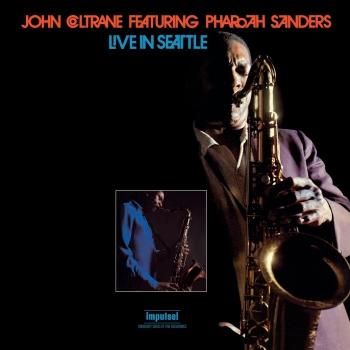

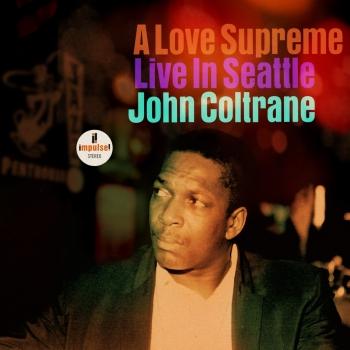

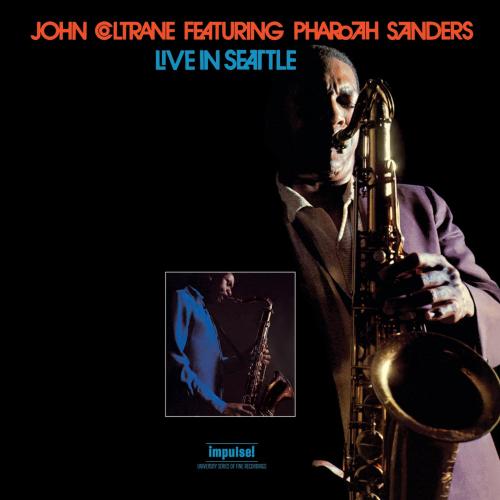

Live In Seattle (Remastered) John Coltrane

Album info

Album-Release:

1965

HRA-Release:

29.09.2017

Album including Album cover

I`m sorry!

Dear HIGHRESAUDIO Visitor,

due to territorial constraints and also different releases dates in each country you currently can`t purchase this album. We are updating our release dates twice a week. So, please feel free to check from time-to-time, if the album is available for your country.

We suggest, that you bookmark the album and use our Short List function.

Thank you for your understanding and patience.

Yours sincerely, HIGHRESAUDIO

- 1 Cosmos 10:49

- 2 Out Of This World 23:41

- 3 Evolution 35:53

- 4 Tapestry In Sound 06:11

Info for Live In Seattle (Remastered)

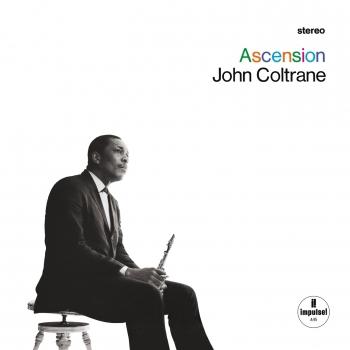

John Coltrane arrived in Seattle on September 30, 1965 with his classic quartet—pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison, and drummer Elvin Jones—plus a couple of friends he'd run into in San Francisco a few days earlier. Seemingly on sudden impulse, Coltrane added to the band free-honking tenor saxophonist Pharoah Sanders and multi-instrumentalist devotee of Eastern religions Donald Rafael Garrett. They were there to play a gig at the Penthouse, a jazz club at the corner of First and Cherry. The album that resulted, Live in Seattle, is such a relentlessly raw and abrasive document of late-period Coltrane that it can be a challenge to listen to the whole thing. (I dare Melvins fans to get through the 36 minutes and 10 seconds of "Evolution.") In a way, it also marks the beginning of the end for the classic Coltrane quartet, a band universally ranked as among the greatest jazz lineups of all time. Since forming in 1962, the quartet had played with guests before. Sax and flute player Eric Dolphy toured with them in Europe, and Coltrane had that summer recorded Ascension with a wild, 11-musician ensemble (including Sanders). But Coltrane was now entering a realm so far out that his loyal comrades—with whom he'd recorded A Love Supreme, Crescent, and My Favorite Things—could no longer follow. What he was after was pure feeling, beyond notes, and certainly beyond anything so mundane as swinging and chords. For this, Sanders was an ideal collaborator, and would squonk and squeak alongside Coltrane until the latter's death in 1967. Tyner and Jones, however, would leave the band by January. Said Jones of his departure, "I couldn't hear what I was doing . . . all I could hear was a bunch of noise." As a benchmark in this unraveling (or progression, depending on your perspective), Live in Seattle almost sounds like two different records. The extended screamfests with Coltrane and Sanders on their tenor saxes and Garrett on bass clarinet are more or less in line with the sound Coltrane would pursue until the end. But there are also long passages without the two newcomers, in which the classic sound reasserts itself. During Tyner's pulpit-pounding solo on "Afro-Blue," the old rhythm section locks in with crystalline clarity and exhilarating propulsion. Veteran DJ and patron saint of Northwest jazz Jim Wilke was there that night. He reports that the Penthouse jazz club was crowded, but may not have been a sellout. Cannonball Adderley's appearance the week before had been a much bigger deal. "To some people, Coltrane was still Miles' former tenor-sax player," says Wilke, who was broadcasting the show on KING-FM as another installment of his weekly show "Jazz from the Penthouse." What about the question that's fixated a particular segment of Coltrane fans for years: Was he tripping? Coltrane had started taking LSD during this period, according to biographer Lewis Porter. But to Wilke, the whole band seemed to be straight. "That may have been my own naivete. I might not have recognized if someone was tripping," he says. "But to me they just seemed like a bunch of experimentalists. Coltrane came off the stage at one point and asked for the headphones (to check the mix that was being broadcast). He said it sounded good, and said, 'This may go on for more than half an hour' [the length of the radio show]. Because he didn't want me to interrupt the music with an announcement from the stage." Not exactly the attention to detail of someone on acid. After that, "Coltrane never said much, just listened intently. Didn't talk to anyone. It wasn't aloofness though, it was intense focus." If Coltrane did any tripping during his visit here, it was more likely during the recording of a second session that's turning 45 this week. The day after the Penthouse gig, the band went to the home studio of recording engineer and drummer Jan Kurtis, armed with chimes and a copy of the Hindu scripture, Bhagavad Gita, and accompanied by local sax and flute player Joe Brazil. This session—full of chanting, moaning, and fearsome playing by Coltrane that seems to come like an angry god out of a deep cave—emerged as the posthumously released Om. It's probably the weirdest thing that ever happened in Lynnwood. Live in Seattle and Om won't ever be as beloved as A Love Supreme or Giant Steps. Garrett moaning in a voice halfway between a Tuvan throat singer and a dry-heaving hobo is probably the moment in jazz least likely to appear in a Ken Burns–style documentary. But for a lot of fans, it's impossible not to listen to the music of Coltrane as the soundtrack to the story of Coltrane the jazz messiah, the restlessly questing hero and spiritual seeker. (The bumper sticker on the back of my Toyota proclaiming "John Coltrane Died For You" is only partly tongue-in-cheek.) And an essential part of that story is the hero's willingness to rise like Shiva and destroy what he created in order to create the next musical cosmos. That our humble little Mayberry was even a small part of this story is unspeakably cool. So if you do decide to mark the occasion, with or without chemical enhancement, don't forget to also drink a belated birthday toast to our hero, who would have turned 84 on September 23. (David Stoesz, Seattle E-Music News)

„Live in Seattle features John Coltrane at a concert in September, 1965 with his expanded sextet (which included pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison, drummer Elvin Jones, Pharoah Sanders on tenor, and Donald Garrett doubling on bass clarinet and bass). Coltrane experts know that 1965 was the year that his music became quite atonal and, with the addition of Sanders, often very violent. This music, therefore, is not for fans of Coltrane's earlier "sheets of sound" period or for those who prefer jazz as melodic background music. The program comprises the nearly free "Cosmos," an intense workout on "Out of This World," a bass feature, and the truly wild "Evolution." Throughout much of this set Coltrane plays some miraculous solos, Sanders consistently turns on the heat, Garrett makes the passionate ensembles a bit overcrowded, Tyner is barely audible, Garrison drones in the background, and Jones struggles to make sense of it all. This is innovative and difficult music.“ (Scott Yanow, AMG)

John Coltrane, tenor saxophone, soprano saxophone

Pharoah Sanders, tenor saxophone

McCoy Tyner, piano

Jimmy Garrison, double bass

Donald Garrett, soprano clarinet, double bass

Elvin Jones, drums

Digitally remastered

John Coltrane

Der Saxofonist John William “Trane” Coltrane wurde am 23.September 1926 in Hamlet, North Carolina geboren. Sein Vater John Robert arbeitete als Schneider und spielte verschiedene Instrumente zum eigenen Vergnügen. Die Mutter Alice Blair stammte aus einer streng gläubigen Methodistenfamilie. Kurz nach Geburt des Sohnes zog die Familie in die benachbarte Industriestadt High Point, wo der Junge bis zu seinem zwölften Lebensjahr eine überwiegend glückliche Kindheit genoss. Im Jahr 1939 jedoch starben sein Vater, sein Großvater und Onkel, sodass die Familie sich von da an ohne männliche Ernährer durchbringen musste. Coltranes Mutter suchte sich verschiedene Jobs, der Junge zog sich in sich zurück und begann, sich ausgiebig der Musik zu widmen. Er hatte 1938 angefangen, Klarinette zu spielen, wechselte aber unter dem Eindruck von Jazzstars wie Lester Young, Coleman Hawkins und Johnny Hodges zum Altsaxofon. Nach dem High-School Abschluss zog er 1943 nach Philadelphia, studierte an der Ornstein School Of Music, dem Granoff Studio, arbeitete in einer Zuckerraffinerie und jammte gelegentlich in verschiedenen Bars und Kneipen.

Der Militärdienst verschlug Coltrane nach Hawaii (1945/46), wo er mit einer Navy Band erste Aufnahmen machte. Daraufhin hielt er sich mit Jobs in Bands von Joe Webb (1946), King Kolax, Big Maybelle und Eddie Vinson (1948) über Wasser. Während eines Engagements im Orchester von Dizzy Gillespie wechselte er um 1949 zum Tenorsaxofon, hatte aber noch nicht genügend stilistische Eigenständigkeit, um als markanter Solist aufzufallen. Er lernte weiterhin in den Ensembles von Earl Bostic (1952), Gay Crosse (1952), Johnny Hodges (1954), arbeitete sich ehrgeizig nach oben, musste aber aufgrund seiner Drogenabhängigkeit künstlerische Rückschläge einstecken, als er etwa 1954 aus dem Hodges-Orchester geschmissen wird. 1955 wendete sich das Blatt durch zwei wichtige Ereignisse. Coltrane heiratete am 3.Oktober seine erste Frau Naima (1955–66) und nur wenige Tage danach engagierte ihn der bereits als Star des Szene geltende Miles Davis in dessen Quintett. Während des folgenden Jahres entstanden Hardbop-Aufnahmen wie “Miles” (1955) und die legendären “Relaxin' / Workin' / Steamin' / Cookin' With The Miles Davis Quintet”-Sessions (1956).

Es war eine der besten Bands dieser Ära und Coltrane nützte die Gelegenheit, um mit Möglichkeiten der Loslösung von den bislang dominierenden funktionsharmonischen Grundlagen zu experimentieren. Die Forschung prägte für diese Phase den missverständlichen Begriff “Sheets Of Sound” (“Klangflächen”), wobei es weniger um die Erstellung von Flächen als um die Auflösung von Akkorden und die Relativierung der bisherigen Linienbildungen des Hardbops ging. Die Musiker strebten danach, die als einengend empfundenen harmonischen Prinzipien des Quintenzirkels hinter sich zu lassen und Coltrane modifizierte seine melodisch geprägte Technik durch Terzsubstitutionen und andere Verschiebungen (1958–60). Gemeinsam mit Miles Davis und dem Pianisten Bill Evans entdeckte er die so genannte Modalität für sich, eine auf den Kirchentonarten des Mittelalters basierenden Technik der Skalenimprovisation, die der wiederum zugunsten einer nahezu freien Spielweise während seiner letzten Schaffensjahre hinter sich ließ.

So entwickelte sich Coltrane innerhalb nur eines Jahrzehnts vom ehrgeizigen Newcomer zu einem der bestbezahlten Jazzkünstler überhaupt. Den ersten Aufnahmen unter eigenem Namen wie “First Trane” (1957) folgte eine immens arbeitsintensive Phase in zahlreichen Studiobands des ‘Prestige’-Umfeldes. Coltrane löste sich 1957 erfolgreich von seiner Drogensucht, wurde mit Thelonious Monk im “Five Spot” umjubelt, kehrte 1958 zu Miles Davis zurück und nahm 1959 nahezu zeitgleich die beiden legendären, aber stilistisch komplett verschiedenen Alben “Kind Of Blue” (mit Davis) und “Giant Steps” auf. Auf “My Favourite Things” entdeckte er 1960 das Sopransaxofon neu für den Jazz und nach dem Auslaufen des Vertrages für die Plattenfirma Atlantic formte sich 1961/2 das klassischen Quartett mit McCoy Tyner (p), Jimmy Garrison (b) und Elvin Jones (dr) als idealen Arbeitsbasis heraus, das Coltrane in seiner Suche nach neuen Ausdrucksformen unterstütze. Mit der im Dezember 1964 aufgenommenen Hymne “A Love Supreme” machte Coltrane seine tiefe, religiös geprägte Spiritualität, öffentlich und Alben wie “Ascension” führten ihn im folgenden Jahr schließlich zum freien Spiel.

Als er sich immer deutlicher der kompletten Auflösung der Form zuwandte, veränderte sich auch sein musikalisches Umfeld. In der letzten Lebensphase war er neben Garrison mit seiner zweiten Frau Alice Coltrane (p), Rashied Ali (dr) und Phaorah Sanders (sax) auf der Bühne zu erleben, späte Werke wie “Expression” oder das Schlagzeug-Duo “Interstellar Space” (beide 1967) präsentierten ihn als introvertierten Hermetiker mit Hang zur spirituellen großen Geste. Am 17.Juli 1967 starb John Coltrane an Leberversagen. Sein markanter, harter und zugleich flexibler Ton, die ekstatische Solistik und Hinwendung zu Einflüssen jenseits der afroamerikanischen Stiltradition hinterließen ebenso wie die Entdeckung des Sopransaxofons als Ergänzung des Tenors viele Impulse für die Klangentwicklung des modernen Jazz.

This album contains no booklet.